[mashshare]

John Rogers: Can you each tell us where you grew up and who you have been working with this past summer?

My name is Melissa Figueroa, and I grew up in Kings County, in Avenal, California. I was interning at ACT for Women and Girls.

My name is Anai Paniagua. This summer I was interning in CHIRLA, the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights in Porterville, California. I grew up in Richgrove, which is in Tulare County.

My name is Crystal Gomez, and I grew up in Fresno. This summer I was interning with Californians For Justice.

I’m Jose Orellana from Delano, California. Currently I’m a third year student at UC Santa Cruz. I interned at the Center on Race, Poverty and the Environment.

My name is Jared Semana. I grew up on the south side of Stockton, right next to the aluminum oil district that was destroyed in the 1960s. I interned this past summer with Fathers and Families of San Joaquin, which is an organization dedicated to, among many things, disrupting the school to prison pipeline.

My name is Lidia Gonzalez, and I am a third year student at UC Merced. This summer I had the honor of interning with the Center on Race, Poverty, and Environment, along with Jose.

How do you describe the Central Valley Freedom Summer project—what is it, and what is its purpose?

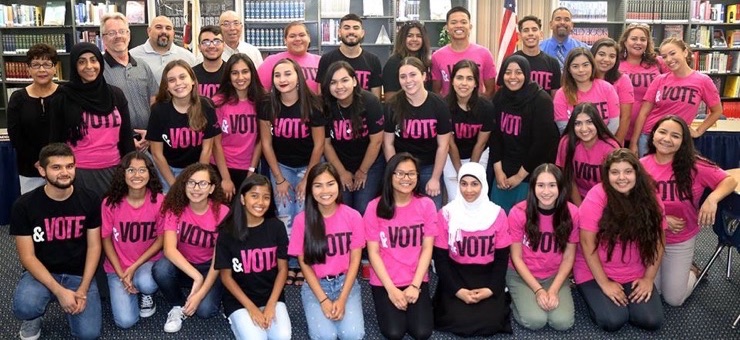

Jose Orellana: The Central Valley Freedom Summer is a research and organizing project that brings together students from UC Santa Cruz and UC Merced and who hail from the Central Valley of California. It places students in community-based organizations across the Central Valley that focus on civic engagement, youth advocacy, and registering and increasing the voting population of the Central Valley. We study and draw upon the legacy and lessons of the 1964 Freedom Summer that happened in Mississippi, which was run by the Student Non-violence Coordinating Committee (SNCC). We utilize the same principles and apply them to the context of the Central Valley, because the Central Valley has a lot of problems that are usually ignored. What we’re trying to do is draw attention to youth civic engagement and increase the voting population.

Jared Semana: When you examine the voting disparities within the Central Valley in the 2014 midterms, older white people voted at almost seven times the rate of youth of color. The Central Valley Freedom Summer in a lot of ways is targeted towards closing those disparities, by building up participation in voting in such a way that would be more representative of the communities that exist here.

What drew you to this project and made you want to commit your summer to doing this work?

Anai Panigua: That’s an easy answer for me. I’ve been working with Dr. Terriquez for over a year, and having had opportunities to attend a few youth conferences with her across the state got me really interested. Usually in those conferences, the Central Valley is never represented—at the ones I went to, there was always me and maybe three other students. I wanted to bring some of the workshops they have in those conferences to the Central Valley, because there aren’t many organizations that prioritize and invest in youth here. We’re out here now and want to change these conditions because we never really had those opportunities.

Lidia Gonzalez: I was able to meet Professor Terriquez who travelled from Santa Cruz all the way down to Merced to talk to us about this project. It was important that her focus was on the Central Valley. I had never heard about anyone being interested in the Central Valley before. That really inspired me to get involved, and to go back home and let others know about this work.

Melissa Figuero: Like Lidia, I felt like there weren’t any programs like this that represented the Central Valley. Being from a really small rural community in Kings County, I thought this could be really important—going back to my town, as someone who is representing not only Kings County, but Avenal. Which is funny, because before any of this, I thought, I’m never going back to Avenal. Whatever I do this summer, I’m not going back home. But this was a chance to represent my community.

So Melissa, what led to that change? You never thought you would go back, and yet here you are. What prompted that?

Melissa Figuero: It was the entire project, and having someone like Dr. Terriquez who believed in us. Her belief actually helped me believe that people from the Central Valley can make a change. Then, just seeing all of the students who are part of this project, and are from the Central Valley. The Central Valley is huge, and most people don’t even think about it. The students I worked with for so many months were so dedicated to making a change, which sparked that same drive in me. It made me believe that I can go back to my community and do this work—I have people that believe in me here and now, so why not start?

Jared Semana: As others have already spoken to, part of what made the Central Valley Freedom Summer very special is that most people don’t necessarily think about the Central Valley when it comes to social or political issues, but there’s a long and rich history of organizing for social justice through the Central Valley. Organizers with ties to Stockton like Philip Vera Cruz and Larry Itliong who were very much a part of the United Farm Workers movement. They were able to organize across the Central Valley and inspire people to realize that they have the capacity to make change. Being from south Stockton, which has had a large Filipino community and tradition of Filipino organizers since the early 20th century, and recognizing the present problems of the Central Valley and connecting them to the past that I feel like I’m very much rooted in, it became clear to me that this project was the best way to honor the people who have inspired me the most.

Jose Orellana: I think I have a completely different reason from everyone else in the project. I was passing by a building on campus and I just saw this flyer that said, “Central Valley Freedom Summer.” And it said, “four thousand dollars, internship, research.” Dr. T hates it when I say that I got into this because of money, but it’s the truth. What that shows is the lack of opportunities to get this kind of paying job, and a lack of opportunities to do research as well.

So initially, I wanted to get that money, make some new friends, and spend some time in the Central Valley. From there, honestly, it has completely changed my life. I’m better at communicating. I have a purpose in life. I love what I’m doing right now.

Jose, aside from the four thousand dollars—which is really important—in what way has “your purpose in life” changed, as you put it?

Jose Orellana: Before Central Valley Freedom Summer, I didn’t even know what I was going to major in, let alone what I was going to do with my life. Like others have mentioned, when you go to these conferences there are all these youth from Northern and Southern California and like three people from the Central Valley. I know how lucky those other kids are to have an established civic infrastructure for youth, and opportunities to be empowered, to get engaged, to change their environments. My purpose now is to continue studying, and continue building a civic infrastructure for young people like myself.

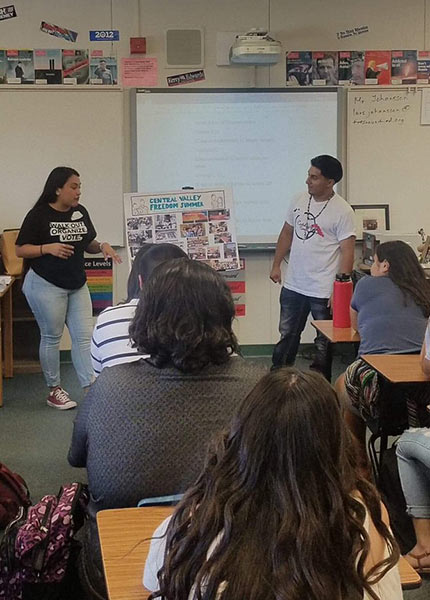

Crystal Gomez: Thank you Jose for the honesty. I think what drew my attention to the Central Valley Freedom Summer was different as well. I was drawn to the voting aspect of it, because I grew up in a household where voting wasn’t really talked about. I also went to a school where I was never told that my voice was important. What drew my attention was being able to go back to that high school and actually talk about the importance of voting with students, which led to some of those students becoming interested in starting a club. Like Jose said, the work doesn’t stop after the Central Valley Freedom Summer is over, because these students are really, really engaged. They want to make a difference in their schools.

I’d like to ask you about something that Professor Terriquez and Randy Villegas wrote in an Op-ed for the Los Angeles Times a couple weeks ago. They point out that the vast majority of young adults in California say they plan to vote, but only 16% voted in the June primaries. How do you make sense of this gap? What do you feel like needs to happen for more young people to make it to the polls?

Jared Semana: There’s a difference between articulating why voting is important versus why voting is relevant. Everybody believes it’s important to vote for things like the presidency, because presidents set policies. But things that are local are really relevant—things like voting for the school board and city council. Those officials decide how much is invested and where it is invested in our communities. Talking about voting in local elections makes it more relevant, and showing youth how there are disparities in our communities when it comes to investing in things like green space, funding for school programs, things like that, helps to build their interest as we outline the process of registering to vote and clarifying questions around it.

Jose Orellana: About two weeks ago we passed the “Empowering and Preparing Young Voters for a Stronger Democracy” Resolution which will give access to non-partisan groups like Loud4Tomorrow or Central Valley Freedom Summer to go into any of the three joint union high schools and register voters. The L.A. Unified School District passed something similar, and that’s where we got the idea. Up to now it’s been really hard going into high schools and doing presentations and voter registration. There are barriers like having to submit your PowerPoint two weeks in advance, and there’s a new rule where you can’t even do presentations during school hours—any type of presentation.

This project also helps empower students, because we created a youth voter council to hold the school board accountable to follow the resolution. The district leadership has to make sure they supply students with voter registration cards, with pens, with voter education literature, stuff like that. We really want to make sure the youth are involved in every policy process. We wrote in the youth voter council because we want to create shared power between students and district leadership.

As you were trying to get this resolution passed, did you experience any pushback? Did any political forces try and stop you? If so, how did you respond?

Jose Orellana: No, it was pretty easy to pass the resolution because a lot of our board members listened to us, and they were supportive of our ideas. We didn’t have a lot of resistance in Delano.

Lidia Gonzalez: I was able to work with Jose this summer, getting youth involved in Kern County, which is very conservative. We faced a lot of resistance going into high schools and trying to let students know about voter engagement, and why it’s important to vote. Initially I was able to go in, but I found that you kind of have to go in saying that you’re there to speak about college, not “I’m trying to register students, and this is why it’s important to be registered.” The first time I did that, they told me that we have to give them at least two weeks notice to be able to return to their the campuses. I never experienced that in high school—presenters would come in without any obstacles. Coming in as part of Central Valley Freedom Summer and trying to educate youth about voting, I really faced resistance.

A couple of years ago, Professor Terriquez led a study in which she asked young adults if they voted in the last election. If they said yes, she asked why, and if they said no, which was very common, she asked why not. Amongst those that said no, many said that voting doesn’t matter. Did any of you get that response from any young people you interacted with, and if so, how did you respond?

Anai Panigua: When I did presentations I got that response a lot. In the Central Valley, people often don’t know about local elections even though local elections matter a lot. Sometimes they would ask, “where do I find this information?” And that is important because every vote matters. I’ll use my little town for an example. Literally in my town only 13 people regularly vote because it’s a really, really small town. So that’s an example of how one vote matters, and local elections really matter. They affect you in every sense.

This also has to do with the lack of infrastructure for civic engagement in the Central Valley. Trying to find those resources on voting is really difficult, even for me as I was doing this work in my town. It was hard for me to find that information, and most people don’t have time to do all of that extra work.

Crystal Gomez: When we were presenting at the high school, most students had the mindset that voting is not important. We used the College for All Act to stress why voting is important. When we asked how many were interested in pursuing higher education, or how to take out loans to attend college, we found that a lot of them were really interested. We brought up the College For All Act because it didn’t get enough petition signatures to be on the November ballot. And that’s when I think we got the most questions, and the most student interest.

Jared Semana: In Stockton, we encountered the same mentality. I tried to help them connect elections and the landscape in Stockton—the issues that were present in their minds already. One thing that I heard was that, on the north side of Stockton, there is a golf course that a small minority of citizens use and costs the city close to a million dollars a year to maintain. They juxtaposed that with issues present in south Stockton, like lack of basic infrastructure—things as basic as sidewalks and streetlights. Investing in schools when there is a literacy crisis in Stockton.

While illustrating how voting relates to investments in schools had a significant impact, so did talking about things like the election for Sheriff, because those elections help shape policies and collaborations with ICE. Many communities in Stockton are very vulnerable to this administration’s position on immigration and status. Stockton has one of the largest Cambodian populations within the country, so this is very pertinent. So thinking through how to center the experiences of people in your community, and specifically youth, are ways to rile folks up to ensure they vote. A lot of traditional discourse about why it’s important to vote emphasizes one’s duty as a citizen, and those things are very preachy and don’t activate youth voting in a meaningful way.

Let me pick up on Jared’s point about the importance of centering discussions around the experiences of people in the local community. I was thinking about that in light of some of the strategies that national organizations will be using in the next month in swing districts like those in the Central Valley. People from L.A. or New York for instance will robo-call people in the Central Valley and try to connect with them and encourage them to vote. That is a very different strategy from what you did this summer. Does it make a difference for young people to engage other young people in their own communities? Does it make a difference when this is done face to face?

Jose Orellana: What gets people past the tipping point is the peer-to-peer contact. The importance of having local youth talk to other local youth has become very clear in our research with Central Valley Freedom Summer. Having local youth running voter registration booths is a very effective way to get young people to register. No one listens to young people better than their peers—those who share their classrooms, go to the same schools, who look like them. What’s going to determine the 2018 elections depends largely on how we strategize our narratives to get people out there to vote.

Melissa Figueroa: I’m currently canvasing and phone banking in King’s County with ACT for Women and Girls, and this past week, we were doing this in Visalia. I noticed that when we would go to houses or call people, their first reaction was, who are you? Where are you from? What do you want? When I did phone banking and canvasing in Avenal, people approached me a lot better—it was much more like, “Oh my gosh, how are you? What are you doing here? I’m so glad you’re doing this work!”

CVFS Merced Conference from Aria Zapata on Vimeo.

Many of you have spoken about the significance of being able to do presentations in high school classrooms and encourage young people to register. Being not too far removed from high school yourselves, I am wondering if this work led anyone to reflect on what may have helped you forge a deeper understanding of the civic and political contexts around you in your own high schools? If this rings true for anyone, imagine that you’re speaking to the teachers and the principals who will read this: what practices would you like to see in high schools that would help young people forge political identities? What practices would build understandings about the importance of being civically and politically engaged while in high school?

Crystal Gomez: For starters, I would like to see classes that speak to the social issues affecting our communities. In Fresno, there are a few high schools that have those kinds of elective classes, but at my high school they don’t have them yet. Those classes would have made me more aware of the issues affecting my community, instead of waiting until I left for college to learn about them. Another thing is to have clubs and workshops that focus on these issues, and to provide opportunities for youth to attend conferences. That’s been a really big opportunity for me.

Jared Semana: Growing up in Stockton, like many of us from the Central Valley, I always wanted to leave–mostly because of my community’s reputation, according to the dominant narrative. I had no interest in investing in my community or organizing. What changed all of that for me was taking Ethnic Studies in college—having that kind of deep, introspective look at what it means to be Filipino and Filipino-American in the context of places like the Central Valley. That was a life changing moment. It engrained and clarified for me why folks need to be engaged and politically motivated. And centering one’s identity in the organizing community and tradition makes that engagement much more potent.

Investing in classes like Ethnic Studies and providing opportunities like Crystal was talking about that center around local issues is key. That’s a form of political education, because it helps students and adults contextualize what the youth are going through. The chance to have mentors and clubs that can guide organizing activities is key, because that too provides outlets for that kind of political socialization, which many times can be very frustrating. Learning about your community sparks a fire in people, and it is vital to an outlet for that.

I’m angry about how my community has been overlooked and disinvested from, and that is also why I used to be ashamed to be a part of my community. My response to it now is asking, how do I organize? How do I change this so that other youth don’t go through the same things? Sometimes building a love for one’s community can only develop through things like ethnic studies classes.

Jose Orellana: Our hope is that this is going to become a reality with a new bill, AB2772, that is currently on the Governor’s desk.* Hopefully he signs it ASAP. If so, more students in California will be able to take Ethnic Studies.

Lidia Gonzalez: I would have liked more of a focus on electoral engagement in our high school Civics classes. In Delano, Civics classes don’t speak to the value of voting. History classes don’t stress how important changes happened because people came together and voted. They don’t emphasize how, over time, people of color fought for the right to be able to vote. I remember a high school teacher who said about that legacy, “We’re not necessarily going to talk about that, because you’ll learn about it when you get to college.” I stopped and looked around, and others were also in awe. We just couldn’t really comprehend that we were being told to wait. We thought the teacher was playing around, but no. In so much of the Central Valley, students go to college and struggle with things like this because we’re not taught about them in high school. It is so important to have teachers who really care and aren’t complacent. Teachers need to have conversations with the school board members who dictate what is taught in classroom settings. That way, teachers can teach about things we care about and we wouldn’t have to wait until college to learn about them.

Anai Panigua: Attending Porterville High School, we didn’t have Ethnic Studies. I feel like our administration and teachers never really listened to us. They never prioritized what we were thinking about or feeling. Usually when someone was in trouble, they never even had a chance. I got in trouble one time and I wasn’t even the person that messed up, they were confusing me with someone else and they didn’t ever listen to me. It was like I had no voice. And I know my peers felt that too.

I had the privilege of being in some AP classes, which were mostly made up of the affluent white kids in town. They were excited enough to be in those classes and learn because they already believed they were going to attend college, and they knew that AP classes would get them there. In my other classes it was mostly low-income students who didn’t have college in mind. I was also fortunate to be in AVID, which prioritized us reaching higher education—it was all learning about and doing scholarships, applying to college, ways of helping with all the tests. But in that class there was only 25 of us, and in my graduating class, there were over 500. I know we didn’t have enough resources for everybody, and I wish that we did. My friends didn’t have the privilege of being in AP or AVID classes, so I would be the one trying to help them, reminding them about classes or deadlines that were coming up.

And like Jared said, we didn’t have counselors trying to push us to consider what comes after high school. The normal expectation was to graduate high school and then, usually what happens is you end up [working] in the fields, or if you’re a female, you just start your family.

Jose mentioned 1964’s Freedom Summer in Mississippi. In what ways do you feel like your experiences like the Central Valley Freedom Summer was similar to or different from the ’64 example?

Crystal Gomez: One similarity is that the ‘64 Freedom Summer wasn’t only about getting folks to vote—it was also teaching them about their culture. It was also about teaching them how to read and write critically, things they were never really exposed to. Like us, they hosted conferences, even though their workshops focused on different cultures and different identities. But the main difference is the level of danger. We have a lot of resistance in smaller communities, but I’m really thankful that we didn’t have anyone go missing. It wasn’t as extreme as it was in the Freedom Summer of 1964 because then people did go missing. People did die. But across both Freedom Summers we see how powerful civic engagement is: There’s always going to be someone in the way, trying to stop others from voting.

Melissa Figueroa: Like Crystal was saying, it was obviously more violent and people died in ’64. Still, there were things for us that were very challenging. When I started I thought that I’d go back to Avenal and nothing bad could possibly happen. I told myself it’s going to be really easy and the community will support me. I know my town. And then I realized that I was wrong, completely wrong. We were already doing voter registration in spring, around March, and that was the first time I tried to get into my high school to do a voter registration. I emailed the principal and the teachers, and no one responded. I thought, I’m just going to step away and wait for the summer.

Then I found out that during the summer, we were not able to go into schools at all. I felt that the people in charge were just not supporting me because I was a woman and a person of color. Maybe they were feeling intimidated. And that’s when I felt that connection with the ’64 Freedom Summer, because I saw how those challenges are still here. They’re still continuing.

And I noticed that it wasn’t just the school that was making this process really challenging, it was also community members and the City Council. They are all older, white people that have lived in this town for many years, holding the power. They saw a young, woman of color, and their response was: “No, we do not want you to come and register these people. We don’t want you to come to this town because you’re going to bring some type of change that we don’t want to see.” So, it wasn’t as violent here as Mississippi in 1964, but I still felt that discrimination, which was really tough and really challenging.

How did you deal with that?

Melissa Figueroa: Staying positive and not giving up. A lot of the time I was by myself, and I felt really overwhelmed because there were so many people in my town that just wanted me to leave. I couldn’t understand it, because I had never experienced that before. And a lot of the people in this town have known me since I was little. That forced me to stay as professional as possible, and trying to get people in my community to get involved and offer some support. I continued working to show them that I just wasn’t going to stop.

Jose Orellana: We’ve learned how to be organizers, politicians, and leaders in our communities. I’m not a fortune teller, but I already see it continuing. Melissa and Jared are leading amazing causes in their community.

You are the legacy, much like the participants in the Mississippi Freedom Summer were the legacy of organizing back then.

Let me read a quote from Professor Terriquez, from an interview I did with her last year. She said, “Mobilization and organizing is now occurring in ways that would’ve been unfathomable two decades ago. I think it’s an opportunity to start mobilizing and building consciousness among a broader public, including among residents in the Central Valley. And to start envisioning the kind of world we want to live in, and get more people to realize that they have a role to play.” When you reflect on this summer, to what extent do you feel like you’ve had a chance to envision a new kind of world you want to live in? To what extent do you feel like you’ve had a chance to have a role in building that world?

Crystal Gomez: I am really thankful that this summer gave me the opportunity to meet so many talented young people who aspire to great things. We tell them that they can be whatever they want, and that also means they don’t have to leave and forget about where they’re from. It’s true that these youth face many obstacles. But we try to show how more opportunities are available as long as we speak up about it. A lot of people believe that young people don’t care. They do care, they just usually don’t know where to start. No one ever tells them that they can speak up and make a change. Even though many of the youth that I met can’t vote yet, they have friends and family members who have that opportunity.

Jared Semana: In response to how we were able to help create the world that we want to live in, voter registration, at the end of the day, is a medium. It’s a medium for us to go into schools and attend conferences and talk about our communities. The education component of it is the key. We did a tour of the Central Valley with these conferences, up and down—and you can see in the students’ eyes, whether it’s in conference workshops, Ethnic Studies workshops, or in classroom presentations, that we’re speaking to them in a way they’ve never been talked to before. I mean that in the sense that we are from the communities they live in; we care about these communities, and we look like them. Being able to educate young Filipino-Americans about the history of the Central Valley, and their history in it, is something I would’ve wanted in high school.

If the turnout in the upcoming election is high in the Central Valley, we might feel that we’ve done something really important; but even if the turnout isn’t what we hoped, what we’ve done is still significant because we’ve been able to activate youth. It’s led to continuing partnerships like those we’ve made in Stockton with teachers and people who are organizing and building those identities. And they know what they’re doing. That, at the end of the day, is the most significant thing I’ve loved about Central Valley Freedom Summer: it’s seeing the change and the hope in each of these youth’s eyes when we talk to them, because they see that we are them. That’s the most important part of creating the world I want to live in, because it leads to communities having access to things they never had before.

As we are now at the end of the summer, some of you are heading back to school, but some of you are staying in these communities because you graduated. What is it that keeps you hopeful at this moment?

Jose Orellana: Knowing that people like Dr. Terriquez and other organizers that I’ve worked with exist, and that they are doing this work that can benefit whole communities. Thinking of all of the people of color and low-income people who are doing the tough work it takes to start anything. And people like us, who are continuing these traditions and continuing to strive for liberation and education.

Melissa Figueroa: I’ve already seen real changes in Avenal with youth getting involved, participating in conferences and in our events. I’ve seen so many people and young adults come to our events, and when they see how we talk about the importance of youth empowerment, I can see that spark in their eye. I want to continue doing that. Because it’s the youth in my community that give me hope that we can have better communities in the Central Valley.

Lidia Gonzalez: I agree with all that Melissa and Jose said, and I also think about the community organizers we had an opportunity to work with. If it weren’t for them, I wouldn’t have known where to start or how to do any organizing. Knowing that they’re back home continuing the work that they have been doing for many years gives me hope that it’s going to continue, especially as youth are becoming very involved.

Anai Panigua: We’ve been able to meet so many youth, and even in the short time we’ve known them, they’ve grown so much. Of course I don’t know what they’re going to do after high school, but I feel like they already have the motivation to make a change in whatever ways they can. That keeps me hopeful, and I’m excited to go back and see the great things that they’re going to do.

Thank you all so much. I really appreciate the time you’ve taken today, and I also want to thank you not only for participating in this conversation, but for the work you’ve done this summer. It’s inspired me and I know the difference it will make in the lives of your community. So, thank you all for that.

* Editor’s Note: On September 30 2018, Governor Jerry Brown vetoed AB 2772, a bill which would have created a pilot Ethnic Studies initiative in several school districts. See this article.