Issue Editor: Natalie Irons

Summer 2019

“Grey Autumn” – designed and quilted in 2017 by the late Karen Lee Lummus, teacher and literacy coach in the Lancaster School District for 33 years.

How does a coach know they are impactful?

At UCLA Center X we have had the opportunity to learn from two decades of coaching educators. In this XChange issue we have displayed our learning as coaches and our support of coaches within the framework of a continuum. We have learned from the educators in our professional learning settings that coaching is in part the ability to hold onto varied perspectives, like seeing the “forest” and the “trees”. We know that coaching requires high levels of awareness of self and others. The work represented here is a reminder that humans are complex and our thinking, our choices to take action, to make decisions about strategies to use and our conscious and unconscious behaviors all make up who we are and who we want to be. Coaching is a fluid act of negotiating all the complexities of educational settings. This XChange issue provides readers a holistic view of educator support by outlining coach capacities where each “continuum” gives examples to the fluidity of the work of a coach.

How does a coach know they are impactful?

At UCLA/Center X we determine our influence within a framework that identifies three areas of focus; the what, why and how we support educators. These three areas live on a fluid continuum that allows coaches to self-reflect, assess and know the ways of their influence. This range includes different approaches and ways of thinking a coach has in their work. We offer a metaphor of seeing “the forest AND the trees”. While the idiom says that people sometimes “can’t see the forest for the trees”, coaches at UCLA Center X propose that coaching is a fluid act that is inclusive, broad while focused, and outside the conventional and historical understanding of many coaching models. Therefore, the following areas of coaching, framed as capacities, are essential to understanding the impact of our work.

Coaching Capacity # 1: To think about coaching as a way of being with educators and holding positive presuppositions for their capacity to be effective.

This means coaches value the people they support as human beings first, so that they can coach for both content and identity. Educators benefit and grow in their work when they know the content they teach, as well as, when they reflect on their identities as educators. This continuum is our “what” of what we do.

I am sitting with a teacher in a 7th grade ELA classroom who has asked essentially the same question over the course of the year about how to teach a particular concept effectively. Setting aside my own frustration that we have been around the subject of teaching “theme” multiple times, I take a breath and say, “This is a complex topic to teach adolescents.” A resounding, “Yes!” fills the room. Then I offer a question, “What are some things you know about yourself when teaching complex ideas?” She sits back and says, “I really need to slow down and teach the concept from another angle and I think I have been repeating the same thing over and over that is not getting through.” Instead of telling the teacher what I did, or offering a dozen ideas about teaching theme, I acknowledged, understood and supported from an approach that holds positive presuppositions that educators have strengths from which to build. This snapshot of a coaching exchange allows the teacher to think about the “what” and “how” they do their work AND “why” they do the work they do. An effective coach listens for these areas of content, pedagogy and identity of the educator in developing their own capacities.

In another recent coaching conversation, I asked a principal, “As you think about the past year of support, what might be most significant to you as a leader in moving forward?” This question focuses on the identity of the principal in reflecting about the role. Contrast that question with the one I heard a director ask of a leader, “What did you do this past year that produced the results you achieved?” While this question is reflective, it focuses more on the external reflection. Oftentimes a coach asks questions that access the “what” or “how” only, like how things get done or “what” was accomplished, and less on the internal thinking of one’s identity. Coaches at UCLA Center X know the value of offering questions that ask about the significance of being a leader to provide an opportunity to think about values and identity.

One of the coaching models we draw from to support educators in thinking about identity is as a Cognitive Coach. This model, one that is supported by 35 years of research and practice by Robert Garmston and Arthur Costa, assumes that educators have capacity and experiences to inform who they are, what they do and how they work. A Cognitive Coach knows how to access resources in others through thinking practices that encourage self-directedness. Coaches give careful attention to others by listening in productive ways, paraphrasing and asking questions about thinking provide opportunities for teachers, administrators and support staff to check in on who they are and want to be as educators (Costa and Garmson, 2016). This close examination between what is and what is possible provides the growth space for change.

Capacity #1 for us is inviting people to think about who they want to be. We do that by “coaching for identity”, in addition to coaching for “content and pedagogy development” as noted in our continuum metaphor. Thinking back to that principal and the coach’s question about identity, the principal responded with a long pause and then said, “Hmmm, I want to think more about that as I create my planning for next year and then talk with you again, so that I can really think about how I will support people next year and how that might change my role.” The response confirms our learning that always focusing on ways that educators can get their work done will only live “at the surface,” without the opportunity to live “below the surface” for greater meaning. Coaching for identity IS the way to actionable work where this fluid concept serves a coach from the bottom up, rather than the other way around.

Coaching Capacity #2: Maintaining successful coaching relationships is both acknowledging one’s position in the interaction and the diversity within each educator. The coach then makes adjustments to meet people where they are.

This means checking on assumptions/biases/filters. Listen and observe first. Asking the question, “How might my identity, both internal and external, impact a coaching interaction?” is vital to this continuum and speaks to the “why” of our coaching.

At UCLA Center X we recognize the assets of our surrounding communities and our positionality in relation to others. This frames for our own coaching community a deep value and desire to know and understand the coach’s self in order to understand and support others. We acknowledge that when a coach comes into an educators’ work space using a specific set of tools and structures without first checking in on who they are coaching and what they value, the coach risks the potential to create a safe space for the coach and educator to have a successful working relationship. Understanding neuroscience research is an important part of this coaching capacity.

Researchers in this area of study of the brain describe that our basic brain functioning makes associations and combs each situation for safety – above all else. Steven Porges, founding director of the Traumatic Stress Research Consortium at Indiana University, uses the term “neuroception” as a part of the “Polyvagal Theory” in which the vagal nerve processes input to detect safety, physically and socially, within the autonomic nervous system; essentially, how our bodies intuit threat, or safety (Porges, 2011). This kind of detection system is extremely important for coaches because this knowledge informs how a coach attends to a person in non-verbal ways, like listening with attention to using tone of voice, or facial and body gestures.

In a recent conversation with a science coach supporting an urban school campus, I noticed a distinct non-verbal shift in this coach. Her eyes averted mine and she gave a subtle nod of her head. I acknowledged that she is “hesitant” to use just one model of coaching, one that other coaches value. She sighed heavily and stated, “I really need to be doing some other things with the staff…my work there looks very different.” She described how as a white woman with decades of educational experience that she needed to build trust, listen to teachers and staff and acknowledge that there might be some identity differences to attend to and adjust for on a campus of students and staff of color. What this coach knows is that her identity awareness is essential to being a successful coach.

When position and race are involved in supporting educators, coaches benefit from what Zaretta Hammond in Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain describes as an “equation: rapport + alliance = cognitive insight” (Hammond, 2015, p. 75) for teachers in the classroom to frame their building of relationships with students. We believe this classroom strategy applies to adult support, as well. When UCLA Coaches enter a campus to support teachers, administrators and other staff members, they are conscious of the ways of the human brain, its primal functioning, and how a coaches’ biases can directly impact a coaching situation.

Coaching Capacity #3: Successful coaching is multi-dimensional, both utilizing a set of tools and structures while also being fluid within those tools and structures.

This means navigating through models, tools, and strategies to support educators in being effective practitioners. These include paraphrasing, asking questions, and/or offering. This capacity addresses structures and tools to support the work of a coach.

Every coach brings a coaching a “toolkit” of strategies to use to support teachers, administrators and support staff. Some coaches are trained in particular models or approaches and do not deviate. Some coaches recognize that some school communities require a multi-faceted approach to coaching. At UCLA Center X, we believe that educators engage in complex, diverse work every day and therefore need support that reflects that complexity. We recognize that the work of supporting an educator needs to be as multi-dimensional as the work itself. We must be the reflection for teachers and leaders.

In order to be reflective, coaches must have a very fluid set of models, tools and strategies from which to draw. Cognitive CoachingSM is one model that encompasses this fluidity. At any given time a “coach” may listen attentively for identity and thinking by paraphrasing and asking questions while simultaneously listening for when someone is “tapped out” or would benefit from hearing another point of view. Sometimes becoming an expert to “consult”, or a colleague to “collaborate” gives an educator an anchor. Cognitive CoachingSM calls these “Support Functions” and in our coaching work these are pivotal in how we focus our attention. (Costa and Garmson, 2016).

Recently when providing coaching support, a math teacher asked me to review a video of her teaching to submit for National Board Certification. She said she had been working on “mathematical talk” in the classroom. I noticed in her facilitating of the math talk, she asked mostly closed-ended questions, like “Did you simplify?” or “Is the reciprocal needed?” Because of the pattern of this way of questioning, I asked her about what she knew about closed and open-ended questions. When she indicated that she was aware of the difference, we listened together again at her questions. She seemed surprised that she heard something different than what she thought she had said. I asked if I could share some thinking. “Yes, please!” she almost begged. “There is a lot of evidence that teachers know it is important to ask open-ended questions, yet still ask closed-ended questions. Remembering to insert a “what” or “how” to begin your questions might reframe them for your students. How might that benefit you in math talks?”

This example describes how as a coach I move along our coaching continuum from a coach who focuses more on the educators’ thinking to a “consultant” who has an eye on a valuable teaching tool, one which I see clearly that the teacher sees with less focus. This movement is very fluid and adaptive. It requires a coach to be vigilant in listening for where the educator is in their thinking, content knowledge, pedagogy and identity and when it is important to insert additional knowledge, perspective and background. Without this vital coaching capacity, the other capacities are less meaningful and impactful as a coach. We need clear tools, strategies and structures from which to draw or we stagnate, repeating the very ways we hope to impact as a coach.

We believe our support is deeply rooted in our ability to develop our own capacities, attend to our own learning and adjust for others to meet them at their learning space. Our continuum of coaching support is an evolution of 20 years of supporting educators, teachers, administrators, paraprofessionals, support staff and parents across districts and organizations and our learning, as evidenced by one UCLA Center X math coach who recently shared in a support meeting, “What is valuable to me and important about being a Center X coach is that I get a chance to learn and grow. I guess that’s why I stay even when it’s hard.”

Coaching questions for our readers:

- When has coaching been impactful for you?

- What are some ways you are attentive to others to reach their capacities? How might your identity impact your coaching relationships?

- When you think about your toolkit of coaching strategies, which ones are most impactful and how do they vary across each educator?

Costa, A. & Garmston, R. (2016). Cognitive coaching: Developing self-directed leaders and learners, (3rd ed). Lanham, MD: Rowman & LIttlefield.

Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polygal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. New York: WW Norton.

Natalie Irons is the Associate Director of Instructional Coaching Programs at UCLA Center X and a Training Associate for Cognitive CoachingSM and Adaptive Schools with Thinking Collaborative. She has held National Board Certification since 1999.

CONTINUUM OF COACHING:

Coaching is for Teachers

Coaching is for Everyone

This continuum addresses “who” receives coaching.

Articles – “What We Do?”

Articles – “Why we do this?”

Origins of Coaching at Center X

James Berger, UCLA Center X Professional Learning Partner History Coach

May 3, 2017

Was it a labor of love, a love of labor, or both? The origins of coaching at UCLA involved some important social and political changes, a cadre of caring and concerned educators, and an intense desire to promote social justice in the challenging environment found in urban schools of the city of Los Angeles.

Two key events in Los Angeles created a spark to demand more action to create a care for social justice in Los Angeles urban schools. First, was the 1992 uprising in areas of South Los Angeles due to the failure to convict members of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) for the brutal beating of motorist Rodney King. Second, was the 1994 California voter approved Proposition 187. This ballot measure denied public services such as public education and healthcare to all undocumented residents of California. In November 1997, Judge Mariana Pfaelzer ruled Proposition 187 unconstitutional because it infringed on the federal government’s exclusive jurisdiction over matters relating to immigration in California.

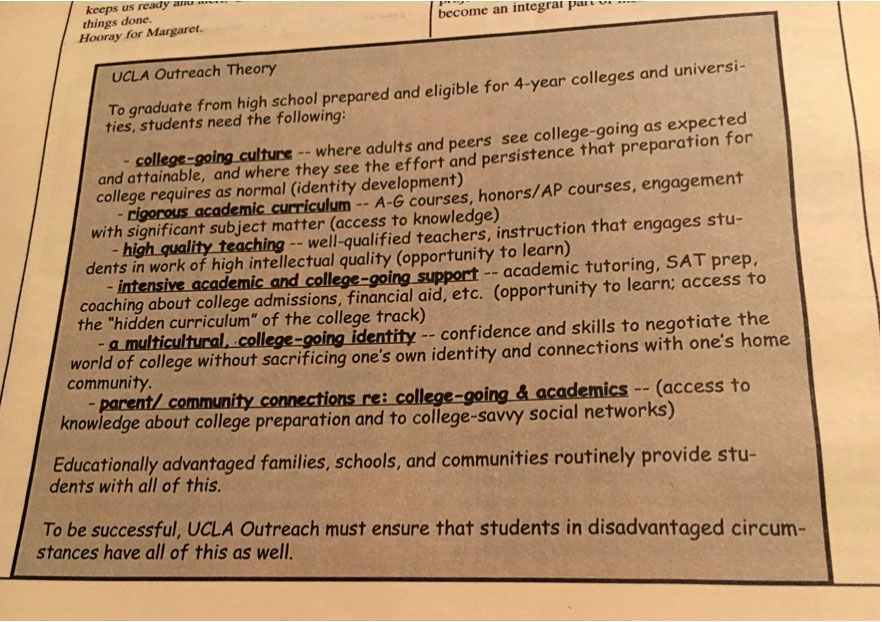

Dr. Jody Priselac, former Executive Director of UCLA’s Center X and adjunct professor in the Department of Education at UCLA and current Associate Dean for Community Programs with UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, thought that Proposition 187 was one of the key factors motivating UCLA’s Graduate School of Education educators to start Center X. In addition, the impetus and birth of UCLA Center X was formed in 1994-95 partially to respond to the “inequity and poor educational practices” in some urban schools. The demands for equity and parity support the fight for social justice in the classroom as well as in the community. As a result, UCLA Center X became the start for intense teacher candidate recruitment for the Teacher Education Program in 1994 (TEP), the Principal Leadership Institute in 2000 (PLI), and California Subject Matter Projects in Writing, Reading, and Literature, Mathematics, Science, and History/Geography. In a 2009 article by Karen Hunter Quartz, Jody Priselac, and Megan Loef Franke about transforming schools, they stated that “Since its’ founding, the Center’s professional development work has developed district partnerships to support teachers serving the lowest-achieving students.” In 2002, Cognitive Coaching became an important tool at UCLA Center X as part of a service to give direct support to new as well as experienced teachers.

In a recent interview with Dr. Priselac, she stated that the first vision and goal of UCLA Center X Coaching was to “work to partner in schools to improve academic achievement.” Dr. Priselac added that some of the key people who started the coaching program with her at Center X included Megan Franke, Susan Hakansson, Faye Peitzman, Anne Sirota, Janet Thornsby, Frances Gibson, and Jane Hancock. Many of these talented educators came from the Center X literacy projects.

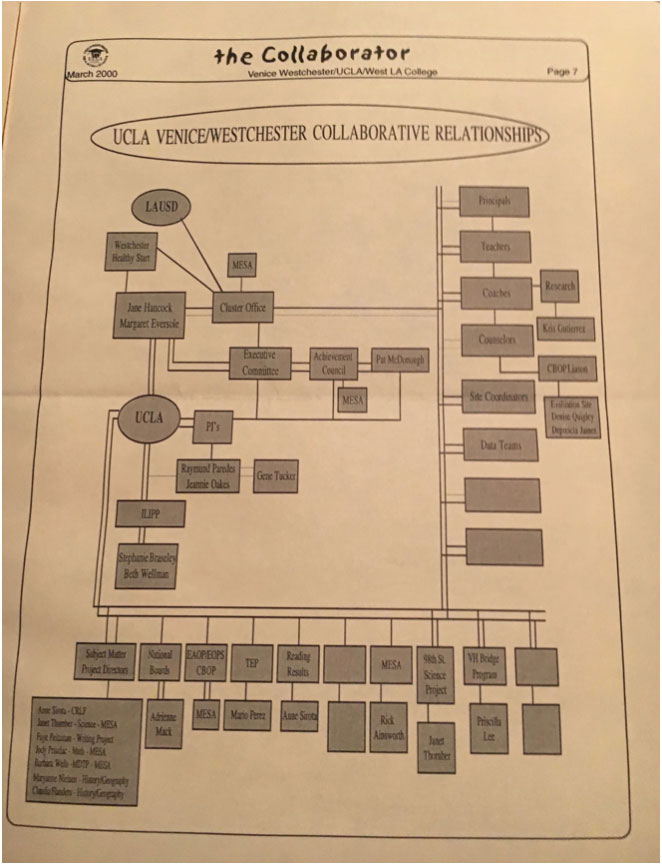

In an extensive interview with Jane Hancock completed by UCLA Center X Professional Learning Partner Susan Strauss, Jane Hancock as Co-Director of UCLA Center X Writing Project stated, “I had been doing workshops for the Venice Westchester/UCLA Collaborative and came up with the idea that, in order for the partnership to accomplish what we wanted to accomplish, we would try literacy coaches.” According to Jane Hancock, there were key factors in looking for a coach. “I looked for people who were innovative and who could seize the moment.” This led to Jane’s book group. Jane stated, “It seems like I recruited everyone that was in my book group to become a coach.”

The first Writing Project coaches came from Jane choosing all Writing Project Fellows and one from the Reading and Literature Project. These coaches for the Westchester schools included “Sydnie Myrick, Norma Mota Altman, Caitlin Rabanera, Kim Marantos, Robin Wisinski, Karen Caruso, Jennifer McFarland, Frances Gipson, and Kim Mitchell.” With some models and a little book on coaching to use, the group decided to write their own coaching book. After learning how to talk to teachers, the group used the Cognitive Coaching and Adaptive Schools strategies with Carolee Hayes.

According to Jane Hancock, coaching was “all about making a connection.” This was the key as well as the key challenge of “establishing the connections,” which is always the key to any professional relationship.

These talented team of educators worked tirelessly with educators like Dr. Sylvia Rousseau. Dr. Rousseau was a former Principal at Santa Monica High School, former Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) Administrator District 7, and former Instructor at UCLA Center X. As an Associate Director of the LAUSD/UCLA Partnership, she was instrumental in connecting UCLA Center X with particular schools in the former Local LAUSD District 7.

Dr. Rousseau wanted Literacy and Math coaches who were connected to UCLA Center X to provide direct support to classroom teachers with model teaching examples of “scaffolding using Bloom Taxonomy including the California State Standards and the goals of No Child Left Behind.” UCLA Center X agreed to “provide trained instructional coaches who provided instructional support “in the three C’s of content, context, and cognitive demand.” Later, the coaching program expanded into former LAUSD District 3. Today, the UCLA Center X coaching program provides teacher support services in Los Angeles area school districts and specifically in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) schools located in South Los Angeles, East Los Angeles, and the San Fernando Valley.

Together the Center X teams collaborated, planned, and organized programs to train educators who wanted to become instructional coaches in order to provide direct support to classroom teachers. They spent countless hours, weeks, and days planning how coaches might be trained, briefed, and placed in specific schools that might best support the success of teachers and administrators. This benefit would lead to greater teacher success in the classroom as well as higher teacher retention with improved student achievement. After classroom observations, coaches provided this direct support by engaging with the teacher in productive reflective, planning, or problem re0-solving conversations. In addition, support might be in co-planning a lesson, co-teaching, modeling a lesson, providing standards-based instructional resources, or collaborating in the development of a classroom project or lesson or school-wide program.

The Coaching Program worked along with a Partnership with many urban school districts. “To help further build relationships with both schools and districts, Center X had developed strategic partnerships with local districts across Los Angeles. This relationship included school-based workgroup meetings and on-site in-classroom support.” Specific forms of support included after school Professional Development (PD) for teachers as well as direct support inside and outside of the classroom. Coaches usually led or co-led professional development in their respective departments or subject matter areas. Teachers “learned to integrate content literacy strategies and standard-based instruction.” These PDs served teachers in all grade levels and all subjects in the core curriculum such as English/Language Arts, Mathematics, Science, and Social Studies.

According to Jody Priselac, the effects of coaching were assessed and measured from “2001 to 2008 as Center X Faculty worked with UCLA evaluation experts to study the implementation and effects of this partnership on context-embedded teacher learning, and ultimately student achievement at the high school level.” The study produced some significant results. “During the six years of the partnership, we saw changes in teacher practice that demonstrated teachers’ understanding of the importance of engaging students with text,” says Priselac. UCLA Center X continues to provide support for classroom teachers as well as make a significant impact with classroom instruction as both a labor of love and love of labor.

As writer of this article, my first exposure to UCLA Center X coaching was during my final year in 2005 as a classroom teacher at Dorsey High School. UCLA Center X History Coach Ed Sugden offered me support with valuable coaching conversations and collaboration in assessing my history students’ writings from a combined History/ELA research project.

My first experience as a UCLA Center X coach was after I retired from the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) in 2005 finishing a 32 year career teaching history at Henry Clay Middle School and Dorsey High School. Since 2006, I have worked with and supported history teachers in both middle schools and high school of LAUSD located in South Los Angeles, East Los Angeles, and the San Fernando Valley.

Jim’s article provides a historical retelling of the origins of coaching at Center X and the focus on literacy strategies with teachers.

The Beginnings of Coaching at Center X: Interview with Jane Hancock

By Susan Strauss

On October 29, 2016, I interviewed Jane Hancock, former Co-Director of the Writing Project, about the origins of UCLA’s Center X Coaching. As the Director of the Venice/Westchester Collaborative, the university’s initial literacy coaching partnership with the Los Angeles Unified School District, Jane offers a first-hand account of the beginning of the instructional coaching program at UCLA. Through Jane’s evolving leadership, she witnessed Center X coaching transform into its current professional learning partnership with the LAUSD. Since I first became a Center X coach in 2002 and consider Jane my friend, my interest in the history of UCLA’s coaching is both professional and personal. The following is her account of how coaching began at Center X, an outreach program at UCLA’s Graduate School of Education:

On October 29, 2016, I interviewed Jane Hancock, former Co-Director of the Writing Project, about the origins of UCLA’s Center X Coaching. As the Director of the Venice/Westchester Collaborative, the university’s initial literacy coaching partnership with the Los Angeles Unified School District, Jane offers a first-hand account of the beginning of the instructional coaching program at UCLA. Through Jane’s evolving leadership, she witnessed Center X coaching transform into its current professional learning partnership with the LAUSD. Since I first became a Center X coach in 2002 and consider Jane my friend, my interest in the history of UCLA’s coaching is both professional and personal. The following is her account of how coaching began at Center X, an outreach program at UCLA’s Graduate School of Education:

SS: So, Jane, how did the coaching business at UCLA get started?

JH: I had been doing workshops for the Venice Westchester/UCLA Collaborative, when we came up with the idea that, in order for the partnership to accomplish what we wanted to accomplish, we would try literacy coaches. At that time, we really didn’t know anybody else who was doing it at all.

SS: How did you come to know about the concept of literacy coaching?

JH: At that time, an education consultant named Dennis Parker, a former California Department of Education administrator and UCLA School Management Program professor, seemed to be the guru on coaching so he came and spoke at our conferences several times about the value of coaching teachers.

SS: How was the first collaborative formed?

Once we had our first literacy coaches, we planned a conference in the summer of ’99, at which Parker spoke. Though the literacy coaches we’d hired had not yet started to work, we did so much research on how coaching might play out that we planned and advertised the conference, invited people to come, and people interested in coaching came.

Once we had our first literacy coaches, we planned a conference in the summer of ’99, at which Parker spoke. Though the literacy coaches we’d hired had not yet started to work, we did so much research on how coaching might play out that we planned and advertised the conference, invited people to come, and people interested in coaching came.

SS: How did you realize the value and need for coaching?

JH: In the partnership’s first newsletter, “The Collaborator,” I explained that “Coaching allows teachers to collaborate on change rather than trying to work on something new in isolation, offers opportunities for continual follow-up, allows for one-on-one professional development and allows students to observe teachers working together to help the students in their learning and to improve their own teaching skills.”

SS: What was the perspective of Center X at UCLA on this coaching venture?

JH: Everybody wanted to get on board. Jeanne Oakes, the Director and Founder of Center X, was the one who hired me to be the Director of the Collaborative because they needed somebody to be the liaison between Center X and the District. So I went to all the principals’ meetings. Eventually, the Venice-Westchester Collaborative became a part of it. Then we began talking about literacy coaches. Later, it became ‘coaching,’ not ‘literacy coaching.’

SS: Was that a good thing?

JH: Not for me. I thought that you needed literacy in science. I always thought of this as being how we get kids to read science texts and write about science. This is how we get kids to read math and write about math. This is how we get kids to read P. E. and write about sports. I always thought about it as literacy. Is it literacy for the math and science teachers, or is it how to teach math, how to teach science? Is it literacy? Is it still literacy? When it started out, it was definitely just literacy.

SS: How did the coaching network reflect the mission of Center X, particularly the focus on social justice?

The mission statement for Center X is “We are a community of educators working to transform public schooling to create a more just, equitable, and humane society.

JH: Making everybody read and write certainly improves their chances any place they go. In the first newsletter, Center X Director Jeannie Oakes wrote an article that explained her goals for the collaboration between coaches and teachers at the Venice Westchester campuses. She stated that “in order for the collaborative to make a difference, it must pursue two strategies simultaneously.” First, she believed “enhancing the existing opportunities in school, no matter how marginal the improvement, can make a tangible difference in the lives of your people and their communities.” Second, she urged that the Collaborative provide “the courage to make the profound cultural and political shifts that equal educational opportunity requires. The diverse young people we teach–-and the rest of us–-deserve no less.”

SS: What did you look for in a coach?

SS: What did you look for in a coach?

JH: I looked for people who were innovative. Who could seize the moment. And that’s hard to define when you’re interviewing someone. Or looking at someone. Just in conversation, that might come up. Like, what have you done in the past that might have seemed at the time risky or off the way but turned out to be good? I think that experience maybe should have been, not experience as a coach because no one had that, but experience as a teacher because some of our coaches were brand new at teaching. They were just good. And we knew they were good. They had the skills and were willing to try new things.

SS: How did you know where to look for coaches?

JH: It seems like I recruited everyone that was in book group to become a coach. I think what was great about the coaching that we did was the way we brought them together for the Cadre meetings. When it was just Venice-Westchester, we met at Webster in a classroom building. So it was just about thirty people, but then later when we got to be big, and we were eighty, ninety people, we met in Culver City.

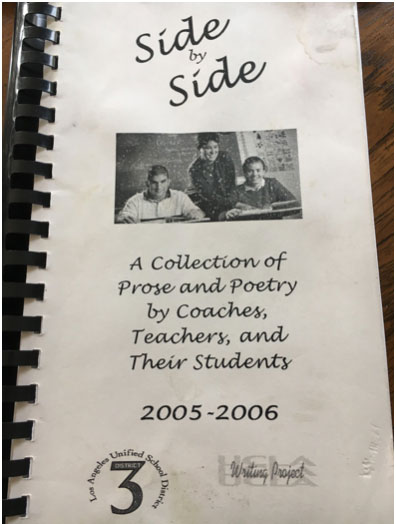

Another thing that set us apart was that we had the Language Arts Cadre writing anthology, Author’s Night, and Open Mic Night. Although I worked with coaching at other districts, they never had that, and I think that really gave us a goal that we were looking for. That spread to where schools had their own anthologies like you did at Marina.

SS: Those were good times! Were the first coaches Writing Project coaches?

JH: Since I was the director of the (Venice Westchester) Collaborative, I chose all Writing Project Fellows but also included one from the Reading and Literature Project. The first coaches for the Westchester schools were Sydnie Myrick, Norma Mota Altman, Caitlin Rabanera, Kim Marantos, Robyn Wisinski, Karen Caruso, Jennifer McFarland, Frances Gipson, and Kim Mitchell.

Nine coaches for over twenty-four schools. Our thought was to split schools so the coaches would work Monday and Tuesday at one school and Thursday and Friday at another. On Wednesdays, they would get together and talk about what worked, and how they could make it better. They kept a big scrapbook of everything they did, and that plan worked pretty well.

SS: What did you use as a model for coaching?

JH: There were models, and we had a little book on coaching. But, we wrote the book. That’s what those Wednesday meetings were all about. “What are we doing? Did it work? What did you do? Well, I put a note in the teacher’s boxes every Monday morning. Oh, why don’t I do that!”

SS: Yes, whenever I heard someone say something good, I’d say, why don’t I do that? Because I felt like I was in uncharted territory.

SS: Yes, whenever I heard someone say something good, I’d say, why don’t I do that? Because I felt like I was in uncharted territory.

JH: Yes. Every Wednesday when we got together, they would spend the day thinking they had to get the ideas together for Thursday or Friday. Most of the day was just sharing how it worked. That’s when the coaches started learning how to talk to teachers. And that’s when we got the Cognitive Coaching and Adaptive Schools with Carolee Hayes.

SS: How would you describe that early coaching community?

JH: It was always about making a connection. That people want you. Please can you come to my room? Will you come? Because I know that at first people were leery of us. They didn’t need coaches. They didn’t want coaches. Can you come talk to me? Sometimes coaching is just listening.

SS: What might have been some of the challenges?

JH: Establishing the connections. When the coaches first began working at the schools, they were there on the days that school actually started, the days when you don’t teach, when you get your room ready. And they were there with a broom ready, whatever was needed, because teachers didn’t know what coaching was all about yet.

The coaches wanted to find teachers who were willing to have a coach. Some teachers said, “I don’t need a coach.” Later on, they asked for one, and eventually, we got to the place where the coach had a whole school, and no one ran from one place to the other.

SS: Were there other Writing Project coaches?

I checked with all the other Writing Projects in California, and none of them had anything that even looked like coaching. So, as far as I know, we were the first. The coaching developed over time because Venice-Westchester had their own results that they wanted; they were on a big Everybody-Goes- to-College track. A lot of it had to do with visiting colleges and having college nights. But, it also included the Parent Project. We had a great Parent Project at the time. It might have been one of the first Parent Projects. Then we took it to Venice-Westchester. Then in 2002, Venice-Westchester became District 3. That changed everything because it took in many more schools, and we had to hire many more coaches.

It was all about literacy, even the Parent Project in those early years. Every time I went, what they asked me to do was get the parents to write with a piece of text. So even with the Parent Project, I was still doing literacy. We needed to get those parents to read and write and understand what their children are being asked to do. Have them do some of those same activities. I know how much the parents loved the piece we used, Salvador Late or Early. Every time I would use it with different parents, they loved that one. It spoke to them. Most of them spoke English. So sometimes they were English speakers. Sometimes we had a translator.

It was all about literacy, even the Parent Project in those early years. Every time I went, what they asked me to do was get the parents to write with a piece of text. So even with the Parent Project, I was still doing literacy. We needed to get those parents to read and write and understand what their children are being asked to do. Have them do some of those same activities. I know how much the parents loved the piece we used, Salvador Late or Early. Every time I would use it with different parents, they loved that one. It spoke to them. Most of them spoke English. So sometimes they were English speakers. Sometimes we had a translator.

SS: How did the Venice Westchester Collaborative change?

JH: First we had Venice Westchester. And then it became District D, which later became District 3. Then the math became coaches. Then the social studies and the other coaches. But, what I’m familiar with is the Language Arts Cadre, which we only had in District 3. Eighty-ninety teachers. Sometimes coaches, sometimes administrators. I know the schools had to pay for the substitute, but they were willing to pay for the substitute, and sometimes they sent more than one teacher. So, if there were 20 schools in the Venice-Westchester, how many schools were there in District 3? Many more. And if the coach and a teacher came from every single one of those schools, and they did, that room down in Pepperdine was full. Mostly secondary but there were elementary teachers, too. They were all there.

SS: Please say more about the Language Arts Cadre.

JH: Sometimes the Language Arts Cadre was where teachers and coaches were just writing together. Everyone was a learner together. And that doesn’t happen in all coaching situations as far as I know. But, that was the good thing about it, the difference between District 3 and the other partnership with District 7, which started up right after that. I don’t think they had that opportunity to be a student along with their coachee the way they did in District 3. I mean you were all getting ideas from me, and then you were working things out together as colleagues, or as learners together, and I think that was a good thing. But, is that necessarily a part of coaching? It was a part of what we did in District 3. So I have to use District 3 as the model.

SS: What were the essentials in getting a coaching community started and maintained?

JH: I think having the support of Venice-Westchester as well as Center X. I don’t think we could have done it if we hadn’t had the support of the entire collaborative. It wasn’t called a district at that time. They had funding. Their goal was “Everybody goes to college.” And that is not necessarily the goal of coaches. And so our coaches had to do a lot about college. Even the little kids wrote their college statement. They did the trips to UCLA. Sometimes they got to sit in and observe actual classes.

SS: What might be some of the highlights of coaching?

Everything about it was a highlight. It’s something I’m really proud of. We started with nothing. We knew nothing. We put on a conference where we shared our nothingness with other people who knew nothing. We had a workshop where we had scenarios, things that could happen in the classroom. And we acted them out. We had Dennis Parker, the UCLA School of Management professor, who dedicated his work as an educator to “closing the achievement gap.”

Everything was exciting because everything was new and exciting. Each school had a Literacy Cadre where content area leaders met to share literacy strategies and have the strategies fan out through the subject areas. Literacy Cadres. The Language Arts Cadre. Open Mic night. Anthologies. It was all about literacy.

SS: Although Center still has coaches, what has changed?

JH: The districts decided they could do what we did. So they got their own coaches. And their own coaches’ jobs were to see that kids passed the test and to support the Framework. The job of our coaches was to further the goals of the Projects at Center X. So literacy was my goal. At first the other projects were not involved, but before long they came on board.

Then, in 2008, we lost all of our coaches. It coincided with the economic downturn so it had something to do with dollars and the idea the district can do their own coaching. They probably can, but if so, why is it when I did workshops, the people in them told me, “We’ve never had workshops like this before!”

SS: Coaching has changed over the years, in many ways for the better because this time we don’t have to start from scratch. Things had to change, but what is it that remains?

Social justice. Equal opportunities. Reading and writing.

JH: In my opinion, once you teach people to read and write, they can learn. And love it. And are eager for it. Literacy. To me that’s the key. It was all about literacy.

Susan’s interview with Jane Hancock is a personal account of the beginnings of coaching at Center X.

Reframing the Narrative: Exploring Issues of Social Justice in the Math Classroom

By Janene Ward and Theo Sagun

In our work with the UCLA Mathematics Project (UCLAMP) as teacher educators, we are committed to providing professional development opportunities that strengthen and deepen content knowledge, advance and emphasize practices that promote equity and access for all students, enhance and expand teaching strategies, and develop the leadership capabilities of mathematics educators in the Los Angeles basin. Our goal is to provide a variety of sustained and systematic opportunities for pre-K through 12th grade teachers and leaders to build their competence and confidence with not only mathematics content, but also with research-based practices that support student access to and understanding of mathematics content. Therefore, we assume various roles in our work with educators – facilitator, consultant, mentor, coach, and disruptor.

We understand the great responsibility we have in our collaborative efforts with teachers and are honored to engage in the work. Therefore, in the beginning of partnerships with schools and districts, we focus on understanding the school site’s culture, develop relationships to establish trust and rapport, and construct norms for collaboration. Collaboration is not only “integral to the cultivation of new modes of teaching and learning” (Hadar & Brody, 2010), but also helps to create and sustain trust and a safe space for inquiry into practice. Collaboration also increases individual and group efficacy, which are both positively correlated with student success (Bandura, 1993; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001; Whalan, 2012).

Teaching is a very personal act and is inherently intertwined with self-perception, experience, teaching and learning paradigms, attitudes, and beliefs. Opening one’s practice to others is not easy. Additionally, changing one’s practice can prove to be even more challenging, particularly when grounded in deficit thinking and discourse. With that in mind, our goal of creating a safe, collaborative space for teachers is not simply to focus on developing content knowledge and practice, but to also disrupt practices grounded in deficit thinking that privilege some students over others. Therefore, we purposefully engage with the community to co-create a different narrative around what kids can do in the mathematics classroom to ensure that the needs of all students are met and to push back against deficit thinking models and “labels that bestow privilege and marginalization”(NCSM & TODOS: Mathematics for All, 2016). To that end, we have found Lab Sites to be a high leverage structure that supports the transformation of teacher practice and beliefs.

Leveraging Lab Sites.

Lab Sites are collaborative classroom-embedded professional learning opportunities where the “complexity and subtlety of classroom teaching [can be explored and refined] as it occurs in real time,” (Brophy, 2004, p. 287). Within the context of a Lab Site,

…teachers are engaged directly with practice, not only through observing live teaching,but also co-planning it… Teachers’ participation in the laboratory setting that involves co-planning the class, observing the enactment, and reflecting on the enactment in collaboration, proves to be authentic in teachers learning to notice mathematically and pedagogically significant phenomena in the classroom interaction and especially in students’ responses. (Naik & Ball, 2014, p. 42).

Houk (2010) likens lab sites to surgical theaters where doctors observe operations to hone their practice. Within the Lab Site structure, we engage teachers as learners, as practitioners, and as leaders through sense-making experiences with content, applications to practice, and reflection. As teachers participate, they have the opportunity to refine and deepen their content knowledge, knowledge of student thinking and the instructional practices that support, elicit and extend student thinking. And, it is through this reflection and conversation that deficit perspectives are often brought to light.

The following narrative is taken from a Lab Site conducted in an elementary school located within the greater Los Angeles area. Lab Site participants include the regular classroom teacher, one of the authors of this piece, and a fifth grade teacher as an observer. An overarching goal is to provide both teachers the space to observe and interact within the Lab Site to make the process a normative practice within the school. The following is generated from the perspective of the aforementioned author and his interaction with the regular classroom teacher and one of her students.

“I didn’t think she would be able…She’s my ‘low’ student.”

In a 4th grade class, a student named Helen sat in the rear reading a comic book. I approached her while her teacher, Mrs. Lee, conferred with other students. Mrs. Lee and I had co-planned problem solving activities for the students in her class. The primary intention was to the utilize the classroom as a Lab Site to engage Mrs. Lee around students’ strategies for solving a ‘multiple groups’ division problem. We also planned to examine student thinking and discuss prevalent or common strategies students used to solve the following:

There are 9 footlong sandwiches. If everyone gets ⅓ of a sandwich, will there be enough to feed the class?

I planned to engage Mrs. Lee around the idea that her students would generate multiple strategies without explicit direct instruction. This would be a new learning for Mrs. Lee who was pleasantly surprised by the diversity of student strategies without prompting or teacher modeling. Lastly, in order to address inequities within the classroom, I sought opportunities to highlight students’ thinking that might disrupt any deficit notions regarding which students were viewed as “math capable” and who might be viewed as “incapable.”

I then engaged Helen about the explanation she had written on her paper.

Her response was, “…because if you add 9 and 9 ⅓ and divide by 2, it has enough.”

Helen sheepishly smiled at me as she slowly put the comic book back in her desk. I asked her to read the story problem with me while I asked her what the story was about and what the quantities in the story represented. I asked her if she knew the number of students in the class, including the teacher, to attend to the question of “Will there be enough to feed the class?” Helen told me there were 21 students and 1 teacher, so there are 22 people in the class.

She slowly began drawing a rectangle and drew 3 columns with 9 rows. I asked her what the picture represented, and she said that her rectangle represented 9 footlong sandwiches split into thirds which made 27 thirds (27 sandwiches). She even indicated on her picture the number of leftover sandwiches (she shaded 5 thirds, which represent 5 sandwiches that were not assigned to anyone in the class).

I told Helen that I appreciated her thinking, her perseverance, and her explanation of the number of leftover sandwiches. I invited Mrs. Lee to notice the details of mathematical modeling on Helen’s paper and to examine Helen’s thinking. Pleased and excited, Mrs. Lee said, “I didn’t think she would be able to solve the problem. I didn’t think she would be able to do anything. She’s my ‘low’ student.”

Co-constructing a Narrative.

Our approach to work with teachers is rooted in a firm commitment to equity and access. Additionally, we understand the tremendous impact teachers have on the reframing, reconceptualizing, and transformation of mathematics education policies and practices that promote equal learning opportunities and outcomes for all (NCSM & TODOS, 2016). As social justice educators, we recognize the need to co-construct counter-narratives to disrupt the historical and institutionalized inequities and definitions of who can succeed in mathematics. The structure of the Lab Site positions teachers as reflective practitioners.

The interaction above with Helen and Mrs. Lee provides one snapshot of a lab experience that allowed a teacher to reconstitute her perspective on who can do mathematics. Additionally, the lab site provided an opportunity for the teacher to make sense of the mathematics by examining student strategies and the thinking students used to make sense of the problem.

Typically, teachers might approach the multiple groups problem in an abstract and rote way by simply introducing the “invert and multiply strategy.” Mrs. Lee’s interaction with students allowed her to generate more concrete ways of approaching a multiple groups problem with sense making. By examining students’ thinking and the details of their strategies, she made connections between students’ strategies as well as reframed how students are viewed as capable in her classroom.

After her math time, Mrs. Lee confided in me that “The kids who typically use the algorithm had trouble with making sense of why ‘inverting and multiplying’ makes sense in the story. The other students, who I thought would struggle, came up with a lot of different ways to solve the problem — but they could make sense of it.”

Mrs. Lee’s reflection is so important and allows us to press into teacher and student beliefs around what a “successful” and “good” mathematician looks like. Traditionally, students who are quick, who get the right answer, and who use the standard algorithm, are positioned as being good at mathematics. By highlighting the thinking and multiple sensemaking strategies of students, we generate an opportunity for the teacher and students to redefine what it means to be successful in the mathematics classroom.

The interactions with Helen and her teacher provide an example that focusing on what students are able to do and engaging with their thinking can be a way to push back against negative labels and dehumanizing language used to describe students. Openly challenging deficit thinking and eliminating deficit discourse requires trust, collaborative classroom-based professional development, and tact (NCSM & TODOS, 2016). For example, the act of conferring with Helen, discussing the details of the story problem, and giving her an opportunity to make sense of the mathematics, was the vehicle for reframing her competency in her teacher’s eyes.

We believe that all students must have access to multiple meaningful mathematical experiences that allow them to make sense of the world through mathematics. By positioning students as active participants in the co-construction of knowledge and understanding, we transform the traditional paradigm of mathematics learning and instruction. As students individually and collaboratively problem solve, they have the opportunity to engage in each other’s ideas, construct and critique arguments, and develop efficacy as a mathematician. Unlike the traditional orientation in mathematics professional development that places most emphasis on content and pedagogy, our work demands that we partner with educators to co-construct a narrative that tells an asset-based story of student success, ensuring equity for all. We believe we must go beyond this approach to professional development and ensure there is a place for themes regarding equity and access. Although there is little evidence in the research for how to seamlessly integrate issues of equity within a professional development setting for mathematics educators (Battey & Franke, 2015), the Lab Site setting allows us to reframe the narrative, in a safe space, by focusing on student thinking and what students can do (Jacobs, et al., 2007).

References

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28 (2), 117-148.

Battey, D., Franke. M.L. (2015). Integrating professional development on mathematics and equity: Countering deficit views of students of color. Education and Urban Society, 47(4), 433-462.

Hadar, L., Brody, D. (2010). From isolation into symphonic harmony: Building a professional development community among teacher educators. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26 (2010). 1641-1651.

Houk, L.M. (2010). Demonstrating teaching in a lab classroom. Educational Leadership. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/summer10/vol67/num09/Demonstrating-Teaching-in-a-Lab-Classroom.aspx

Jacobs, V.R., Franke, M.L., Carpenter, T., Levi, L., Battey, D. (2007). Professional development focused on children’s algebraic reasoning in elementary school. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 38(3), 258-288.

Mathematics education through the lens of social justice: acknowledgement, actions, and accountability. (2016). Retrieved May 3, 2017, from http://www.todos-math.org/socialjustice

Naik, S.S., Ball, D.L. (2014). Professional development in a laboratory setting examining evolution in teachers’ questioning and participation. Journal of Mathematics Education, 7(2), 40-54.

Tschannen-Moran, M. & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(2001), 783-805.

Whalan, F. (2012). Collective Responsibility. Towards a model for the development of collective responsibility. Sydney, AU: Sense Publishers.

Theo and Janene’s article captures how classroom-embedded professional development becomes a “lab site” for reframing what students can do in math.

Video of reflecting questions/paraphrases

Natalie Irons and Damon Goar’s video shows how coaches coach each other.

Reflection – “What we are learning?”

This continuum illustrates our learning regarding the scope of “who” benefits from coaching. In the beginning of our coaching work, coaches worked almost exclusively with teachers. As we’ve developed as coaches and try to remain adaptive to the communities we support, we acknowledge that our coaching work is for everyone – teachers, administrators, students, colleagues, and each other.

CONTINUUM OF COACHING:

Coaching Happens in the Classroom

Coaching Extends to All Areas of a Community

This continuum addresses “where” coaching takes place.

Articles – “What We Do?”

Articles – “Why we do this?”

How Coaching Impacts Teachers – Monica Williams

By Monica L. Williams

In sports, every team has a coach. A coach’s primary responsibility is to make sure all team members have an understanding of their individual roles and a clear understanding of how to execute those roles with precision. Coaches provide the encouragement and support necessary for each team member to play in their respective positions at an optimal level of performance whether on the court or on the field. The impact a coach has on a player, good or bad, can last a lifetime. John Wooden (UCLA), for example, is regarded as one of the best basketball coaches in history. When commenting on the role of patience in achieving progress, Wooden noted, “We can have no progress without change, so you must have patience.”

Drawing a parallel to the field of education, effective instructional coaches are instruments of progress and have an enormous impact on teachers — which, in turn, maximizes a teacher’s impact on students. In collaborating with a teacher, an effective instructional coach serves as a mirror. This mirroring process assists the teacher in recognizing needed adjustments to methodically implement in order to perfect the reflection shown. Patience is a critical factor to this reflective development process.

In my experience, teachers want to make sure their students are achieving academically, socially, and personally. Making the appropriate instructional adjustments with a coach can ensure those adjustments are advancing the teacher’s instructional development skills while facilitating student achievement.

There are three areas in which an instructional coach can assist a teacher tailor their methods and, ultimately, position a teacher to execute at their optimal level of performance, each of which could translate to improved student learning:

1) Creating a safe, non-evaluative environment for collaboration

2) Assisting with the process of reflection

3) Providing constructive feedback throughout the process.

Once the coach and teacher build a trusting relationship, one that is supportive and non-evaluative in nature, both the coach and teacher operate with a mutual understanding that there is a delicate level of confidentiality between them. This relationship creates a synergy that spills-over into the classroom to empower the teacher to impact students.

1) Let’s examine the safe, non-evaluative teacher/coach environment…

This is the space where teachers feel safe to have a collaborative conversation with the coach. In this space, needs are openly discussed, frustrations with strained resources are confessed, and goals – but more importantly the application steps needed to achieve those goals – are outlined.

As a first step, the coach has to observe the teacher in action to collect data, which will assist the teacher sketch his/her goals. To clarify, a coach should not use collected data against a teacher to belittle, criticize, or reprimand. Instead, collected data is a tool used to qualify the mirroring process. This way, the teacher can see concrete examples of what was done well, what warrants improvement, and what next steps are needed. This is the beginning of established trust in the teacher/coach relationship.

Building on that trust, the coach then offers support through a needs/goals assessment. The needs/goals assessment should be a conversation that invites a dialogue and takes the teacher through a series of questions to pinpoint potential needs and goals.

Sample questions that identify needs might be:

- What concerns might you have about of your instruction?

- What have you observed your students require to learn at their best?

- How might I support you in meeting those needs?

Sample questions that identify goals might be:

- What are three goals you have this year?

- How would you like to see these goals prioritized?

- What expectations of a time-line might you have for these goals?

- Have you taken any first-steps? If not, when would you like to?

- Can you name a past success you had that we could use as a point of reference?

- What type of support might I provide to help you reach these goals?

Once the needs and goals are established, the coach can then guide the teacher through a collaborative conversation to help the teacher focus on outlining an action plan.

2) How a coach assists a teacher with processing the reflection…

The coach begins the process of “holding a mirror” by fostering an introspective conversation that helps the teacher assess whether the top-priority goals are being met and, if not, what adjustments should be made. It is through this collaborative process that teachers become more empowered to achieve their goals and become more focused and self-directed in their development.

Have you ever struggled with the following dilemma: “I need time to analyze if what I’m doing with my students is working.” According to Dr. Jane Bluestein in Why Teachers Quit, part 3 (2013), “Teachers have come under heavy scrutiny and there is tremendous pressure on teachers to ‘get it right,’ and in many settings this has come to mean having their competence reflected in test scores.” I submit that coaches have the ability to ease the tension and pressure teachers are facing through the collaborative mirroring process.

In other fields, including the legal practice, financing industry, and sales, mentors and advisers are offered, if not required through mandatory pairing, in order to encourage an atmosphere where ideas are shared and non-evaluative feedback is offered in a safe-zone relationship. Why should teaching be any different, especially when one considers the very fragile client teachers serve — students? Our children deserve teachers that provide high-quality instruction and offer engaging classrooms. When teachers are provided effective coaching, they can devote more concentration to their craft and to their students. To clarify, teachers can, and have been, perfecting their skills on their own for some time – but the question is, should they have to? As Dr. Bluestein highlights, teachers are often left alone, forced to figure out and strategize by themselves, with little feedback, and while processing fears of being perceived as incompetent (Bluestein, 2013).

Reflection is the key to change…

Depending on the school, teachers are sometimes given time for grade-level meetings and again, depending on the campus; there are also the mandatory weekly Professional Development (PD) meetings. The growing frustration with these meetings, however, reveals the following teacher sentiment, “The discussions in our PD have little to do with ‘my work’ with ‘my students’.” By contrast, with a coach, teachers receive the one-on-one or small group attention they need to specifically and poignantly address their students, improving their practice, and ensuring their identified goals are met:

Having a coach has helped me see the areas where I need to improve. We can sit down together to set goals and make adjustments to my lessons using the standards, student data and the evidence from the coach’s observations. I had no idea I would need this type of support. It has made a difference in the way I teach.

(New teacher, Los Angeles Unified School District (2017)).

Reflection is a cognitive process that calls for introspection, but also requires action. It requires more than just remembering what was done. It also requires using a series of questions to “track your steps.” In the remembering process, reflection is achieved when a teacher thinks critically in determining whether proper steps were taken to reach the identified goal. Reflection is making sure the “in the moment” adjustments are made in order to solidify immediate progress during the teaching process. Finally, effective reflection requires documenting those changes-made in order to refine the teaching the next time around.

Teachers are so busy with day-to-day demands; they rarely, if ever, get to review what they did and, more importantly, how they did it. In “The Reflective Teacher” (Part 3, 2010), Peter Pappas developed a reflective sex-level process that helps teachers create an environment of reflection that takes this cognitive process to a new dimension. These six levels are helpful for teachers to engage in during the reflective process. Pappas derived the levels from Bloom’s Taxonomy (how teachers question students) and subsequently applied each level to teachers reflecting on their practice.

Within this process there are six-levels of critical thinking questions that teachers must ask themselves in order to better their process of teaching. Please see peter.pappas.com (The Reflective teacher: A Taxonomy of Reflection, part 3) to learn more.

3) The critical role and function of feedback…

According to Grant Wiggins in Educational Leadership (September, 2012), “feedback is information about how we are doing in our efforts to reach a goal.” While some would regard feedback and commentary as synonymous, feedback goes beyond providing mere commentary and requires a more directive, yet balanced approach. These seven points are essential in order for feedback to be effective.

If our feedback is going to make an impact, it must be:

- Goal referenced

- Tangible & transparent

- Actionable

- User-friendly (specific and personalized)

- Timely

- Ongoing

- Consistent

Goal referenced: The coach makes sure the teacher is remembering the goals they set together from the goals assessment. It is incumbent upon the teacher to re-visit the goals to have successful outcomes with students.

Tangible & transparent: The way a coach can provide tangible feedback is providing notes that the instructional coach took on a specific lesson. Teachers can also video tape themselves to see if they are meeting their goals. The idea behind tangible and transparent is the fact that changes are necessary in order to improve. Many times we are too busy performing to see if we are meeting our goals. So looking back on our performance through video/audio taping, or reviewing coach notes allows teachers to analyze what they are doing even after its done.

Actionable: It is always more useful for a coach to be specific, concrete and useful according to Wiggins. When the feedback is actionable it is specific to what the teacher wants to happen. It is not vague, and it has to be accepted by the teacher. When a teacher is asked, “what would you like me to look for?” the teacher is in total control of the outcomes, and everyone involved is clear as to what action should be taken.

User-friendly: This is very important to teachers because of the on-going demands with possible behavioral problems, assessment deadlines, grading, meetings etc.…This type of feedback must not be too technical that could cause confusion. Coaches must also remember to give feedback in small increments of information, providing one or two key points so not to overwhelm the teacher. Keep the feedback clear, simple, with few key points and not too technical and the feedback will be welcomed.

Timely: Timing is everything! It is important to give feedback as soon as possible. It is not as effective if teachers receive feedback weeks or months after the performance. It really has no effect if the feedback is received late. It is better if the feedback comes a day or two after the lesson while the actions are still fresh in the teacher’s mind.

On going: How often do teachers get to use the feedback given? If I get feedback often, I am able to make the necessary adjustments to my actions and ultimately get better results because I have more opportunities to try the new suggestions from the feedback, and learn from it.

Consistent: For feedback to be consistent teachers must have a mutual understanding about what highly-effective teaching is and what the expectations are for high quality work. To sustain consistency teachers must use rubrics, anchor papers, and exemplars, so that we are all consistent with the feedback we give. If teachers want our students to be able to give productive feedback, we as teachers must know how to provide structures in our work of that same feedback to our students and coaches to teachers.

In light of these seven essential factors of feedback, it is imperative that coaches be in position to identify ways to help teachers make improvement possible. According to Wiggins, it depends on one being able to adjust their pace when receiving on-going feedback while moving toward a concrete, long-term goal. In other words, for coaches to be impactful we must give on-going feedback regularly, which allows teachers to make necessary adjustments and then provide continuous feedback through the adjustments, in order to propel them to the anticipated goal. It is the non-evaluative environment, reflection and feedback that gives teachers the platform to improve their practice, which will directly affect how our students learn.

Monica’s article illustrates how coaches can support teachers in the classroom through questions and feedback.

Diary of a Not So Wimpy Coach – Damon Goar

Damon’s article illustrates the day-to-day complexities of coaching work and how it extends beyond the classroom.

Five Tips for a Better Professional Development – John Landa

John’s slideshow presentation offers quick and easy considerations when leading professional development.

Reflection – “What we are learning?”

Some of the most direct support of teachers happens when coaches are in the classroom with teachers; planning, observing, reflecting, and collaborating. And in order to support the types of whole school transformations many schools desire, coaching needs to extend beyond the classroom to all parts of the school.

CONTINUUM OF COACHING:

Coaching is for Content and Pedagogy Development

Coaching is for Identity Development

This continuum addresses models that include instructional and content focus, other frameworks of reference, such as equity and diversity and Cognitive CoachingSM which addresses identity, particularly as a mediator of thinking.

Articles – “What We Do?”

Articles – “Why we do this?”

“Writing as a Utopian Concept” – Literacy Cadre – Susan Strauss

The UCLA Writing Project’s Language Arts Cadre (2001-2008)

– Susan Strauss

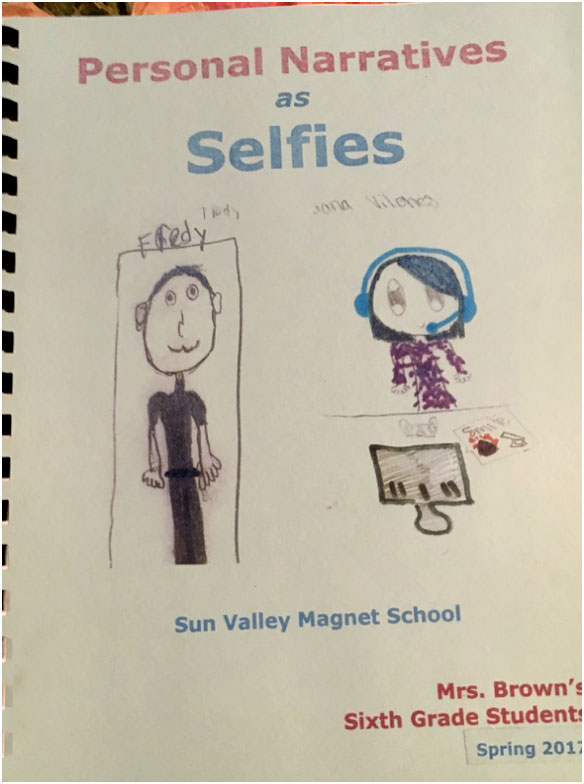

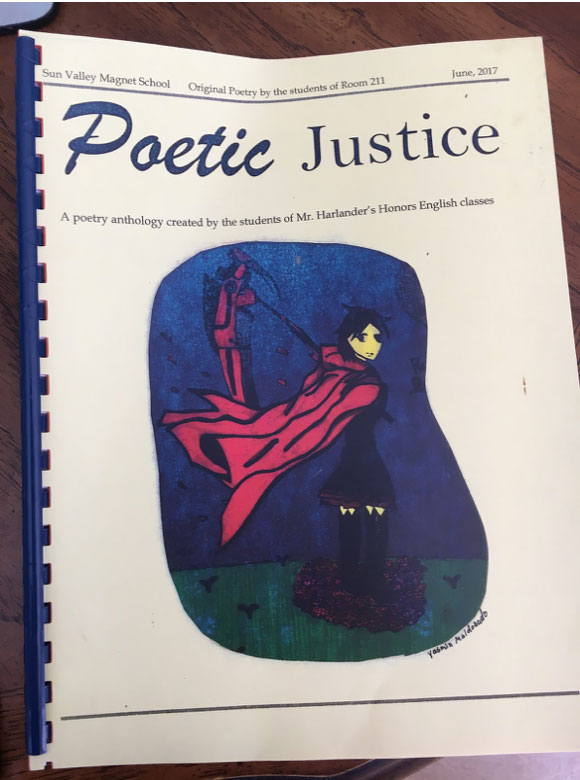

As a UCLA Center X ELA coach at an LAUSD secondary school, publishing student writing and supporting author celebrations are one of my favorite things to do thanks to the inspirational model presented by Jane Hancock, the Co-Director of the Writing Project. From 2001 to 2008, the UCLA-District D Language Arts Cadre, consisting of Jane and local district writing coaches and teachers, met on the first Thursday of the month in an overcrowded room on Pepperdine’s Culver City campus. In collaboration with the local district’s Secondary Literacy team, Jane formed the cadre to create a model for teaching successful writing lessons for teachers and coaches to transfer to the classroom and ultimately improve student achievement. Since making writing public is the best motivation for improving writing, at the end of each school year we submitted student, teacher, and coach writing to be published in an anthology. Following publication, Center X’s Writing Project celebrated the authors’ published writing on campus with an open mic for students, teachers, coaches, and administrators to share their work. Thanks to Jane’s inspiration, ten years later, I am still teaching, publishing, and sharing student writing. In fact, as I write this story of the Language Arts Cadre, it is the last week of school and I am preparing for an eighth grade author celebration called “Poetic Justice” on Thursday followed by a sixth grade one called “Personal Narrative as Selfies” with students and teachers reading from their respective anthologies. Capturing the story of Jane Hancock and the Language Arts Cadre is like trying to grab hold of the live sparks of inspiration, but in the hopes that invaluable history really does repeat itself, here it is.

Every so often some kind of idealized situation enters your life, and if you’re lucky, it plays a recurring role, and if you’re beyond fortunate, it continues. During my first year as a UCLA Center X Literacy Coach, experienced writing teacher utopia in the form of the Language Arts Cadre, a monthly meeting of English teachers and coaches, led by Jane Hancock in partnership with LAUSD’s Local District D, Jane, Co-Director of the Writing Project at UCLA’s Center X, created this writing collaborative as an opportunity for all of us to learn her genre-specific and blended genre writing lessons by rehearsing it as if we were her students, which in fact we were. Next, we collaborated with a teaching colleague to transfer the lesson to the classrooms at our school sites. Her approach to teaching the genres of writing was so original it was as if someone had thrown open the doors of the writing classroom and a brilliant gust of engaging and highly literary writing lessons pumped new oxygen into our tanks and we wrote like crazy during every meeting for seven years. It wasn’t hard to realize that my life as a writing teacher would never be the same. Those particular Thursdays where we spent the entire morning writing and talking about writing easily became my favorite day of the month.

Every so often some kind of idealized situation enters your life, and if you’re lucky, it plays a recurring role, and if you’re beyond fortunate, it continues. During my first year as a UCLA Center X Literacy Coach, experienced writing teacher utopia in the form of the Language Arts Cadre, a monthly meeting of English teachers and coaches, led by Jane Hancock in partnership with LAUSD’s Local District D, Jane, Co-Director of the Writing Project at UCLA’s Center X, created this writing collaborative as an opportunity for all of us to learn her genre-specific and blended genre writing lessons by rehearsing it as if we were her students, which in fact we were. Next, we collaborated with a teaching colleague to transfer the lesson to the classrooms at our school sites. Her approach to teaching the genres of writing was so original it was as if someone had thrown open the doors of the writing classroom and a brilliant gust of engaging and highly literary writing lessons pumped new oxygen into our tanks and we wrote like crazy during every meeting for seven years. It wasn’t hard to realize that my life as a writing teacher would never be the same. Those particular Thursdays where we spent the entire morning writing and talking about writing easily became my favorite day of the month.

As one of the founders of the UCLA Center X coaching network in the late ‘90s, Jane understood the importance of the teacher-coach collaboration as well as the central purpose of Center X where “X” marked the spot where research intersected with practice. She continuously showcased the Writing Project philosophy that teachers should always write their own assignments by sharing her own writing along with student samples or by writing right alongside us as we responded to her prompts. In order to construct a model environment for teachers and coaches to write side-by-side, she created the Language Arts Cadre where we spent the entire morning writing in response to one of her compelling lessons, always simulating a writing classroom where we were the students, and Jane was our teacher. For this particular coach, having a front row seat to Jane’s highly engaging writing lessons, the opportunity to write to her assignments, and the ability to share the experience with like-minded people represented an ideal world.

Surrounded by about eighty dedicated writing teachers and coaches, we wrote like crazy, opening, closing, and filling up the lesson with writing. Like people on a road trip, we only stopped writing for bathroom breaks and crafting revision, such as transforming ordinary nouns for specific ones, or exchanging transitive verbs for colorful active ones. Then we jumped back in and wrote until it was time to find a place to stop. Like the classroom, we shared our writing with partners, table groups, and for those of us who were game, the entire group. Sharing one’s writing was particularly daunting in front of a room packed with masterful English teachers with the sharpest minds and pencils imaginable. But we did, sometimes voluntarily, sometimes with a friendly nudge. We often ended the writing time taking turns sharing our favorite word, phrase, or sentence like a tidal wave from one side of the room to the other. Later, teachers and partner coaches collaborated to plan ways to adapt the lesson to fit the needs of the teachers’ diverse students so we could return to campus ready to roll it out in the teachers’ classroom. We taught, often with the coach modeling the first round, usually reflecting between classes to revise the plan to fit the needs of the next students.

Our focus was always on continuous improvement. Quite often after we implemented one of Jane’s lessons, word spread around the campus that something good was happening and other teachers – English and across the disciplines — found out and wanted in on it. “It was about literacy,” Jane said. “Sure, we were teaching writing, but what we were really teaching was literacy.”

Our focus was always on continuous improvement. Quite often after we implemented one of Jane’s lessons, word spread around the campus that something good was happening and other teachers – English and across the disciplines — found out and wanted in on it. “It was about literacy,” Jane said. “Sure, we were teaching writing, but what we were really teaching was literacy.”

Research-based writing strategies populated all of her lessons, so up close and personal she shared a volley of them with each lesson. Some favorites were The Call of Words, Echo Poetry, Reader’s Theater, Imitation Writing, Literature Circles, Double-Entry Journals, Letter Writing Across the Genres, Say-Mean-Matter, Question-Driven I-Search, Socratic Seminars, Persona Writing, Two-Voice Poems, Random Autobiographies, Dialogue Poems, Pantoum Poems, ABC and List Poems, and Autobiographical Adjectives transformed into nouns as inspiration for Personal Narratives.

Writing assignments ranged from simulating Sandra Cisneros’ “Salvador Late or Early,” to comparing an excerpt from Farewell to Manzanar to one from Snow Falling on Cedars, to savoring, responding, and simulating a vast number of poems by Billy Collins.

There was always a goal. Certainly her lessons’ goals revolved around writing to a selected genre and multiple revisions to improve it. Did we address the California standards? Explicitly and directly. Each week we focused on a selected strategy, aligning the sequencing to follow the genre focus in the classroom. Sometimes, we engaged in genre-switching mid-lesson.

“Let’s get started,” she might begin. “It’s time to write.”