Politics and Hope: Jackie Goldberg on creating fair and adequate funding for California’s schools

In this edition of Just Talk, Center X faculty director John Rogers talks with Jackie Goldberg about education funding in California.

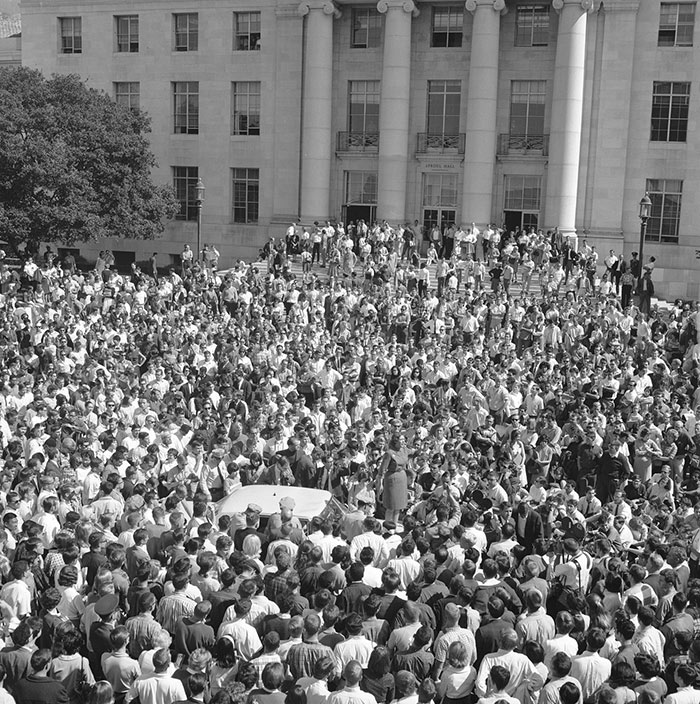

Jackie Goldberg has a long history of working for democracy and equality in education. In the early 1960s, she emerged as a prominent leader in the Free Speech movement at Berkeley. Later that decade, she began teaching in Compton. Throughout the 1970s, she worked to promote racial justice in Los Angeles-area schools. In the early 1980s, she was elected to the Los Angeles School Board where she later served as president. Jackie was elected to the Los Angeles City Council in 1992 and then elected to the California Assembly in 2000. While in the State legislature, she served as the Chair of the California Assembly Education Committee. After retiring from the state Assembly in 2006, Jackie Goldberg joined us in Center X where she taught for several years in UCLA’s Teacher Education Program. She remains a highly valued and trusted advisor to the program.

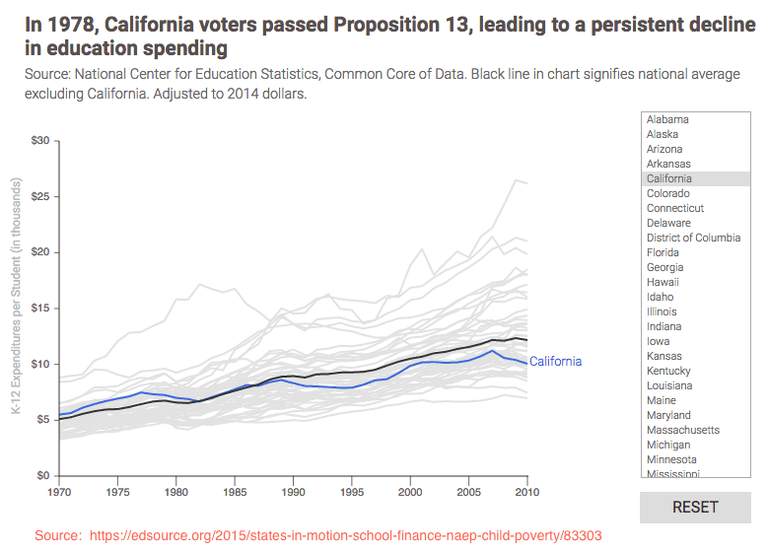

John Rogers: Welcome, Jackie. You have been working for sufficient and fair funding for California schools for nearly a half century. California’s school funding has changed quite a bit during this period. At the time when you started as a classroom teacher in Compton in the late 1960s, school funding in California was in the top 10 in the U.S. When you entered the school board in Los Angeles in the early 1980s, it was slightly above average. By the time you served in the state assembly and were chair of the state education committee in the early 2000s, California schools were near the bottom in the U.S.

Jackie Goldberg: Absolutely. In per pupil spending, one of the years I was in the state Assembly we were ranked 49th.[1]

What happened? Why did we see this decline from the late 1960s to the early 2000s?

It really started in 1978 with the passage of Proposition 13. When Prop. 13 passed, suddenly out of nowhere the local property tax base fell by 6.1 billion dollars, a 53% reduction at the time. It also capped the growth of property taxes and shifted the authority for how these taxes were spent from local actors to the state, and the state legislature effectively became the school board in the sky. This was an enormous difference. Instead of everybody at the local level trying to convince people to raise property taxes to help their schools, any changes to property taxes were now reallocated by the state. For the state, public schools lost a little over two billion dollars. It also meant that you had to go hat in hand to the state legislature to ask for school funding, so people from different districts now had competing goals. These competing goals changed the relationship completely between school boards and the state. The school boards lost a lot of their independence, including power over their budgets and whether or not they were able to afford certain things. Since this time, there has been a sustained decline overall in the ability of school districts to get money, and it’s happened to an extent that is frankly terrifying.

You’ve hinted at some of the possible causes of passing Proposition 13. From the late 1960s and into the 70s, there was the Serrano decision, which sought to equalize funding between high wealth and low wealth districts. Additionally, during the same period there were efforts throughout the state to advance school desegregation. To what extent do you think that pressures to equalize school funding, as well as pressures to desegregate, had any relationship to the passage of Proposition 13?

I think it had a lot to do in general with the public’s attitudes toward public education, and it really marked the beginning of the assault on public education. Now, we’ve had about 45 years where basically the mass media has agreed that public education doesn’t work in California, and it does this by publishing endless stories about educational failure without any notion that there’s any relationship between family income and achievement. We’ve done nothing as a state to deal with the challenges that come from being a family that doesn’t have enough to eat, or doesn’t have a place to sleep at night. There are challenges when you’re part of a family that has to move three or four times every year, which of course means children are switching schools three or four times per year.

When I started teaching in Compton, people were more or less making it (economically) in the late 1960s. This was immediately before all of the aerospace industry moved to the south, because they were looking for lower wages and non-union shops. Before then, California essentially had a recession-proof economy based on the aerospace industry and military spending. During those years, people in places like Compton, where I was teaching, were able to stay put because even if they weren’t making union wages they were making close to union wages. During those years, we saw real growth in educational outcomes. Then, beginning in the early 1970s, people started moving out because the jobs were fleeing—businesses trying to get away from unions and having to pay high wages. So in places like Compton especially, but really throughout much of Los Angeles, there started to be a great deal of economic uncertainty for families. As the (educational) progress of the children in these families began to decline, the newspapers decided to blame the children themselves and their teachers. When this happened, support for funding public education was really undermined.

Since this time we’ve really had a continuous onslaught of stories about “bad teachers” and “bad schools” and “bad kids” and “failure, failure, failure.” Now, what we have are legislators who are only looking out for their own districts, and people believe that no matter how much the state spends, it doesn’t make a difference.

In recent decades we have seen a growing demographic divide in California. The electorate in our state remains primarily white and older, whereas the student body in K-12 schools is increasingly made up of young people of color. To what extent do you feel that this echo chamber of “bad kids” and “bad teachers” emerges from California’s failure to view its growing diversity as a collective strength?

I think those things are absolutely related. The fact is, public school funding in California was the highest when the schools were the whitest. Increasingly, as public schools have become primarily low-income students and young people of color, along with immigrants and English learners, the funding has declined dramatically. And I don’t think that’s accidental at all.

I keep reminding people as often as I can that the last institution in America that says everyone is welcome—and it might well be the only institution left that does this—is the public school system.

In your view, how has the decline in education funding impacted teaching and learning over this period?

Every year, California is between 49th and 51st of all states in class sizes if you include Washington, DC. If you ask any teacher, administrator, or parent whether they’d rather have their elementary school child in a class that has 18 students or 29 students, it’s not a hard decision. Consider that if you’re a parent of a middle or high school student who has classes with 35 kids and class runs for 55 minutes, you’re lucky if your kid has one minute of attention per day. In an elementary classroom they may get ten minutes of attention per day. When I was chairing the state Assembly Education Committee, we would have testimony from time to time about how small class sizes didn’t make any difference. Almost always, this came from a lobbyist who had their kid in a private school with a maximum class size of 18. I would call them out on this. I’d say, “Let me see if I understand. Your kid needs a student to teacher ratio of 18 to 1, with your six figure income. But a kid whose family can barely make ends meet is perfectly fine surviving in a 35 to 1 classroom. Do I have this right?” I believe class size in California should be based on income: the lower the family’s income, the lower the child’s class size.

We need to understand that as a state, when you have the fewest number of librarians and fewest library books per student in the country, the fewest psychologists and social workers per student, and the fewest administrators per student in the country, you’ve designed a school system that only works for children who are in a position to take advantage of an under-resourced school system and overcrowded schools. And some kids can. If your kids aren’t doing well academically and you’re a middle to high income parent, you hire a tutor. If they’re having emotional problems you get them counseling outside of school. If you want them to have a higher vocabulary you travel with them in the summer and read with them at home. But if you’re working three jobs and spending only four to six hours a night at home and your child isn’t doing well, tough luck. You certainly can’t afford to pay for all of the things I just listed. The schools can’t provide these things. So what you have is a situation where you’ve underfunded the entire population that is not at least middle income, and you’re shocked when they don’t do well emotionally and physically, when they see no hope or join gangs, and when there are high levels of suicide and drug use. We’re shocked and dismayed and we can’t understand why “those people” can’t behave more like us.

What are your thoughts about how we talk about education funding—how can we do this in a way that helps voters across California see the issue as one that impacts “we the people,” instead of just a problem for “those people”?

I think that we need to do a much better job educating people about what other states are doing. For example, in 2014-15, Vermont spent $23,149 per student. In the same year, California spent $10,000. If people understood that other states are doing much better than we are in looking after their children, it would make a difference. If you look at what we spend per $1,000 of personal income in the state, California comes in 33rd. Alaska spends $63 per every $1,000 of personal income, while we spend a little under $30.

We need to remind people that California is the 8th largest economy in the world, it’s the richest state in the nation, and yet we have decided that we are a poor state. We behave like we’re a state without resources. If we continue to behave in this way, we’ll continue to reap what we sow. We’ll continue to have huge disparities between rich and poor, more homelessness, more crime, and more mental illness, because all of these things are a consequence of deciding that we don’t need any more resources than we currently have. I think it calls for a really well organized campaign that informs people that our taxes are not the highest in the nation, and in fact they’re not even close to being the highest in the nation. We have the lowest property taxes, almost nothing in the way of estate taxes, and practically nothing in the way of corporate taxes. If you take the average tax bill from the average Californian, we are right around the national average. And yet private firms and lobbyists routinely spread the idea that we have the highest taxes in the country, which is simply not true.

The problem is the overall view that public schools don’t work. There’s this overwhelming belief that we need to get rid of them and start all over again and let the private sector take over. I try to remind people that very recently, the private sector destroyed our economy. It destroyed people’s pensions and the housing market, and we want it to do to the educational system what it’s done to these other sectors?

In 2012, Proposition 30 passed at time when California public schools were really at their nadir in terms of funding. We had an infusion of new money through this bill. And in 2013 we saw the passage of the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) which constructs a framework for more equity in terms of how funds are distributed. What has been the result of these changes?

Well, they’ve had a positive effect. When I left the state legislature I think we were down to about $7,500 ADA and now we’re back up to around $10,370, but it’s still not enough. I mean, imagine what you could do if you had $23,000 ADA—you could revolutionize education, right here in California. What we have now is just not enough.

I think LCFF has been a disappointment overall, because schools haven’t been able to increase parental involvement or empower parents in decision-making. Local school funding formulas work best when the general public is much better informed about what the additional money could be used for. If LCFF is going to make a big difference, we’re going to have to figure out how to let people know that they can have a say in how money is spent. I don’t think we’re doing a very good job of that right now.

We’re coming up on an election with a number of state initiatives, including Proposition 55, the California Children’s Education Health Care Protection Act of 2016, which looks to extend Proposition 30’s personal income tax provision for the next twelve years. In effect, those with the highest incomes will continue to pay a little bit more toward K-12 education and community colleges. The formula suggests that if there is anything left over, it will go toward providing health care for low-income families. Why do you think it’s fair to continue to focus a higher level of income tax on the highest earners?

Proposition 55 recognizes that we have a tax system that, in terms of property, favors the rich. Instead of having a graduated tax based on the value of a property, we have property taxes frozen at, say, one percent of a million dollars on a property that may now be worth two million, which enables the rich to get away with a huge tax break. But even bigger than this are corporate tax breaks, because corporations don’t die, so they are never reassessed. Take for example the oil tank farms in the South Bay of Los Angeles—they haven’t been reassessed since 1978. Do you think that oil prices are the same as they were in 1978?

So, Proposition 30 was one way for the state to even things out a little bit, and it keeps us from laying off another thirty thousand teachers like we did during the recession cuts. Really, it just keeps us in the status quo, which means that we are still horribly underfunded.

Does it make sense to have a proposition that is aimed at investing in education, but sets aside some funds for health care for low-income families?

It does, because even with the Affordable Care Act, a lot of people on Medi-Cal still have copayments that are hard for them to make. If a child gets the flu or needs a flu shot and they can’t get it, they’re going to miss school. In Los Angeles County, the biggest medical-related reason kids miss school is because of a lack of dental care. So it really does make sense to set some of this aside for medical and dental care.

You’ve been an activist throughout your adult life. You came into education with a history of student activism, as a teacher you were an activist, and then you continued working with activists while holding various elected positions. What lessons can you share with young people today who want to work for social justice in education?

First, they’ve got to become informed about the history of how we got into the mess we’re in. They have to understand the economic realities of our state. In the early 1960s, when I went to UC Berkeley as an undergrad with free tuition, California was the 18th largest economy in the world. Now we’re the 8th. We are a richer state than we’ve ever been and we treat ourselves like we are a low-income state with no resources.

The second thing they need to know is that public schools work. They work more than they don’t, and they certainly work more than they should given how little we invest in them. We should be hearing and reading success stories every day of every week about how many kids are doing well in a system that is completely underfunded.

Third, they need to know that as long as people can donate any amount of money to anybody in public office, very little is going to change. We have to get some change in the way that we fund elections. Right now we have so-called progressive Democrats in office who support charter schools in every decision because they’re afraid of the billions of dollars that back the charter schools. We have a Governor who calls himself a progressive who has vetoed legislation that would require charter schools to provide free lunches for students who qualify for free and reduced lunch. That’s fear, and that kind of fear undermines the democratic process. As long as this happens, you create such fear that you guarantee bad public policy, and we can’t continue doing this if we want to provide opportunities for all children to succeed.

Beyond all of these things they need to know, they need to do something about it. They need to join organizations and unions, which, in California, are still relatively strong. They need to press all of the teacher unions to take a more active role in educating the public. The California Teachers Association spends a lot of money every election cycle, but they need to spend money every year. There needs to be radio and TV spots all the time, and unions in other sectors need to get involved as well.

Young activists need to get in a union, raise money, and raise money continuously for a public education campaign that occurs throughout the year, every year. They need to highlight those elected officials who call themselves progressive and yet do not vote progressively on education issues. They need to highlight the damage of having people who are bought and sold who run for office. We need to make it possible for people to run for office on strong principles, and to follow through on those principles, instead of what happens now which really just breeds cynicism.

Thank you, Jackie, for a half-century of struggle around these issues, and thank you for being an antidote to cynicism.

Oh, there’s reason for hope. Young people always give me reason for hope. That’s why I like working with them.

[1] This ranking looked at per pupil expenditures adjusted for the cost of living in each state.

Just Talk welcomes your ideas for other texts to post or interviews to conduct. Send your thoughts to John Rogers rogers@gseis.ucla.edu.

Go to this week’s issue of Just News from Center X.