[mashshare]

In this week’s Just Talk, John Rogers sits down with Mariana Ramirez from the Math, Science, and Technology Magnet Academy at Roosevelt High School in Los Angeles.

In this week’s Just Talk, John Rogers sits down with Mariana Ramirez from the Math, Science, and Technology Magnet Academy at Roosevelt High School in Los Angeles.

Mariana serves as the Social Studies Department Chair and the Common Core Lead. She also is the sponsor of the school’s MEChA Club, and a member of the Politics and Pedagogy Collective.

John Rogers: Can you begin by describing the community where you teach?

Mariana Ramirez: I work at Roosevelt High School in Boyle Heights, which historically has been an immigrant neighborhood, beginning with eastern European and Jewish immigrants, as well as Japanese immigrants and others in the first the half of the 20th century. Since the mid-twentieth century it’s become more of a Mexican or Latino neighborhood, and recently it’s more Latino as more people have come from Central America. Right now, Roosevelt is about 90% Latino. Many folks consider it to be the heart of the neighborhood. Most of my students are immigrants themselves or their parents are immigrants, so immigration is definitely an issue that impacts all folks in the community.

What is distinctive about being an educator in a community like Boyle Heights, which has a large immigrant population? In what ways does that shape your work as an educator?

I am also an immigrant, and even though I’m now a naturalized US citizen, I definitely experienced what it is like to be undocumented and to have parents that are undocumented. That upbringing shaped me first as a human being, and later as an educator, so while I understand what that feels like, I also understand that I have a certain privilege. It’s important for me to demystify our educational system for parents and students, because our educational system is very different from that of Latin America. Constantly speaking to parents and students in a way that breaks down the barriers and steps to get to college, for example, is very important because I know that’s a generational issue. Parents don’t necessarily come with that knowledge, because it’s just not very accessible. As an educator, it’s important to convey how our educational system functions and some of the setbacks my students may encounter. I provide statistics about the proportion of Latino immigrant youth who are thriving within the educational system, which presents a very gloomy reality. I convey it not to depress my students and their families, but so that they can understand it, and together we can consider it as a positive challenge for all of us. How do we change that reality? What can we do, each and every one of us, so that we all can have better access?

You noted that you grew up as an immigrant student. In previous conversations you have described yourself as a “border crosser.” What does that means?

A border crosser is a student who somehow has access to live on the Tijuana side of the border, but attends school on the San Diego side of the border. We had tourist visas and we’d use those to cross the border. We had to be very careful doing that, because we couldn’t cross with books, for example. If we did, it had to be very few books. We had to hide them under the car seat. We had to have a story, like where we were going and why. As children, we understood that what we were doing might be wrong, but it was for our benefit. Some children are US citizens but their parents are not, so they live on the Tijuana side of the border. During high school, a lot of my friends lived in Tijuana, and they crossed the border as teenagers on their own. It was just part of their daily commutes, like living in South Central and going to school in East LA, like many of my students do. There is a privilege attached to that because you can cross the border, but it’s also very daunting for a child or a teenager to do that alone, because immigration agents are terrifying and dehumanizing. They sometimes ask irrelevant questions. And the wait can take forever.

There might be three to four hour waits. All of that impacts how you show up to school. You’re there to do the best you can, but you’ve already been through so much in crossing the border in the morning to even get to school—you just want to succeed, to make your parents proud, and to show everybody that the reason you struggled crossing that border is to do well in school. Oftentimes, in my experience, the school wasn’t very welcoming. I didn’t feel like I was being challenged, and that teachers had a lower expectation of me.

There were televisions in classrooms, and the playgrounds were beautiful, but the learning that was going on wasn’t pushing me to become a better student, or a better human being. I was pulled out for ELD, and I remember that it was a small room—it felt like a custodial room, because there was a lot of brooms and mops in there. It was with another student’s mom, and she would go over the days of the week with me. Being a border crosser, we knew English already from TV, and by the exchange of culture. It’s just a part of what you see every day. For her to teach me the days of the week and the colors, as a child it left me thinking, “Maybe I’m not smart enough.” I wanted to be with the other kids that were learning history or science in the afternoons while I was there learning colors. I still wanted to do the best that I could, even though all this other stuff was happening around me.

Did this early experience shape your understanding of the border?

With the kids I grew up with, we had this knowledge of what the border meant: who can cross it, who couldn’t cross it, and why. Being six years old and having that understanding of immigration policy is something else, right? We might hope that children live an innocent life, but as immigrant border crosser children, you face that reality. You understand how to engage with an immigration agent, for example. Your parents teach you what to say and what not to say. You learn to have patience as a child because crossing the border takes a long time.

Your family has crossed that border for generations, and the border had crossed your family, too, in a way. I’m wondering if you can speak a little bit to this fact, as parts of your story includes history and knowledge that many readers may not be aware of.

My great-grandfather came to Tijuana when it was just a small town, because there was money to be made there. It was being built up to become a tourist attraction for Americans; there was a casino and a racetrack, for instance. Later, my grandfathers on both my mother and father’s side became part of a guest worker program that was created around World War II and lasted until the 1960s due to shortages in labor. The US government went into nearly all states in Mexico and hired workers through this program. Most of them were agricultural workers. Both of my grandfathers worked in the same cities in central California, Guadalupe and Santa Maria. They didn’t know each other, but neither went back to their home states when the program ended, and they ended up living in Tijuana. My grandfather on my father’s side had a green card, but he didn’t use it, and instead gathered his family in Tijuana because there were more opportunities there compared to their small town in Jalisco. Later, in the 1980s, my brother got diagnosed with cancer and the only place to access chemotherapy was in San Diego. My grandfather became a US citizen and requested a green card for my father. Once that happened, my brother got access to the health services he needed and eventually my father requested green cards for us. By the time I was in college, I was able to get a US citizenship through naturalization.

I think of my story of immigration as an exception, because US immigration policy has always been against people of color. For me, a Mexican with indigenous roots in this land, it’s a complicated identity. This land really is an expression of who we are as a people, but history has erased so much of that. US immigration policy has always been exclusionary for people of color, as we can see, for example, in the Chinese Exclusion Act. That my family was able to gain legal access is almost a miracle, just like my brother’s cancer, which has been in remission for years now. All of us think of it as magical—the fact that we were able to get legalized, and the fact that my brother’s cancer could be cured. Most of my students will never be able to legalize their status. I tell my students that I feel like an exception, a miracle. The reality now is a broken immigration system that doesn’t value families and doesn’t value workers. They urged my grandparents to come here and work and exploited their bodies; now others just like them are pushed out through extreme nativism and racism. I tell my students to not lose hope, to consider me an ally and a resource, and that I can resist alongside them while seeking out the best resources I can find. At the same time, I let them know that I understand how daunting it is, and the fear and intimidation that is involved. But it’s useless to cross our arms and stay in one place; it’s better to look ahead and keep moving forward.

Many of the struggles that you experienced and your students are now facing as residents and immigrants—some of whom have legal status, though others do not—are challenges that have been around for several years. In the wake of the 2016 election, to what extent do you feel like our present challenges are similar to those of the past? To what extent do you feel like new sorts of challenges are emerging?

When I was growing up, Pete Wilson was the governor of California and Operation Gatekeeper was underway, which heavily militarized the US-Mexico border. Just walking around my neighborhood was dangerous. At that point I already had a green card, but we’d be stopped, and sometimes handcuffed, just walking to a football game. I’d say, “I live down the street. You want to ask us for our documents? I’m only 15. My mom doesn’t let me carry my immigration documents.” There was just a constant military presence and police helicopters. We would see people cross the border and get harassed and brutalized by immigration agents. I feel like that is nothing new, unfortunately. However, with the election of the 45th president, as well as the advent of social media, there is a lot more visibility for these issues and events. The Undocumented and Unafraid movement and Black Lives Matter, for example, have used social media to shed light on what’s happening in their communities. Exclusions of this kind have been happening for many years, even since the 1920s and the 1940s, when there were massive deportations of people, many of whom were US citizens.

As a teacher, I don’t assume my students come in thinking of these as new or old struggles. But it’s so present, in part because social media has us hooked to what’s happening. It’s a good thing, because these issues are no longer invisible—the brutalization is real, as is the separation of families and the fear. At the same time, it can be daunting for your spirit. When I talk to my students about these issues and how they should think of me as an ally or an advocate, I’m careful to always make space for them to talk about and process how they feel, because it can be paralyzing to live with that fear.

Oftentimes, I turn to restorative justice. Since the election last November, we’ve had several circles. I’m a history teacher, so discussing the reality of what is now happening is also teaching history; working toward students’ understanding of what’s happening, and having them search for ways to deal with and possibly change this reality, is teaching for me.

Are there special skills required to facilitate a Restorative Justice circle?

Restorative justice takes a lot of vulnerability on the teacher’s part, because you have to open yourself up to your students. Even though credentialing programs train teachers to humanize themselves for their students, and to understand their positionality and power, once you get into a classroom it can feel like the whole educational system pushes against those ideas. It becomes a huge, mounting pressure…

A pressure to distance yourself …

To distance yourself from your students, absolutely. It’s that battle of being with your students: to not always be in front of them or talking at them, but to talk with your students. Sharing your story is an important part of this, and as a woman of color, I share my story so they know that I didn’t end up at a university simply because it was destined for me. I want my students to know that my story is part of a whole struggle of people who came before me and helped open doors so that I could become a teacher. This also helps to build a shared community with students; they come to know that they can trust you, and that you’re not so much a friend but an ally who is there to support them in every way that you can.

Restorative Justice circles also build a sense of community between students and provide them with a sense of safety. There are so many issues that come up in urban schools and urban neighborhood because of poverty. We use our circles to discuss these issues, but we also try to think beyond them: What are the causes of what’s happening? How can we change this reality? The most important part of being in a Restorative Justice circle is active listening, and students’ support for one another. I think the ultimate goal is to foster empathy. Today’s society is so fast-paced that it pushes against the value and need for empathy, all while pushing towards more individualistic ways of living. Restorative Justice helps students envision the classroom as a community where we all grow and support each other.

As you’re speaking, I’m remembering a quote from the Mexican educator Lucio Cabañas that you shared with me: “Ser pueblo, hacer pueblo, y estar con el pueblo.”

This translates, more or less, into “Being community, creating community, and living in solidarity.” Can you speak about how that idea informs your work in the classroom beyond restorative justice? For example, to what extent does that vision frame how you approach teaching US History?

Recently, I’ve been reading a lot about ethnic studies and thinking about its meaning. As a practitioner that believes in social justice, I’m used to trying out pedagogical ideas and some of them might become regular parts of my teaching practice. Occasionally I’ll read about these ideas later and learn “Okay, so this is the name for that strategy.” I’ve been trying to practice that kind of teaching, which is a struggle, because it counters the prevailing educational system. For me, ethnic studies is a decolonial way of teaching: it fosters critical literacies, so as a teacher, by selecting readings and types of writing that relate to students’ cultural identities, I’m also allowing them to explore their own individual identities. It’s sociocultural as well, because it involves dialogue and learning together as a classroom community. I am always learning with my students, and they always enlighten me with their fresh ideas. It’s responsive to the community, because I always try to relate our lesson content to issues that come up in the community.

So, how does all of this relate back to US History? I think of it as a decolonial approach, because it begins with understanding that this is indigenous land, that violent interactions were foundational in creating what the US is today, and that with very few exceptions, my students and I are indigenous people. This is a history that has long been denied, removed, or is constantly under threat by efforts to erase it. I find that we often don’t know too much of our indigenous roots. It starts with recognizing that this land is indigenous, and the capital and wealth of this country was built upon slave labor and the kidnapping of African people. Then, understanding how the colonization process became an imperialistic process, which resulted in the US becoming the most powerful nation in the history of the world. I want my students to understand that even though some of this dates back to the 1700s, its impacts are very much with us today.

I know that part of your instruction is also informed by what some people call Youth Participatory Action Research. Can you describe what that approach means to you, and how you integrate those elements into your work with students?

Roosevelt High School, in part because of the spirit of Boyle Heights itself, has had a very activist spirit in this neighborhood for well over 50 years. About seven years ago, a group of students approached me wanting to talk about the educational system, because we were facing massive layoffs at the time. Later, after relaying this discussion to some of my teacher friends and colleagues, we all realized just how many students were concerned and interested. Perhaps not coincidentally, it was around this time the movie “Waiting for Superman” came out, which depicted our school as a dropout factory. So after conferring with my English teacher partner, Alice Im, I asked those students if they wanted to research the educational system, and they happily agreed. They broke off into teams, with each group selecting a theme, and then wrote group papers and created workshops aimed at teaching younger students about the educational system. We started from there, and we’ve been doing this work ever since. It was only later that we learned about Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR)—its history of centering young people of color at the forefront of research, enhancing their capacities and research skills, and providing new means for young people to join together and take a stand. We have come to really love this work and have had great success doing it.

Doing this sort of work with youth can be painful as well, because research is a frustrating process. It’s like writing—both take a lot of work. In our model, we pair the English and social studies departments. There are days or weeks in the school year entirely dedicated to students’ research projects; our role is to find resources and pair students with experts. Sometimes it’s parents or community members who are experts in the topic under investigation. We let the students choose their topics and form their own research teams. I see each stage as containing important skills. Not only are students learning literacy skills, but this work is university-level. Just like I did, many of my students enter high school somewhere between fourth and seventh grade reading levels. So it’s a challenge for them. But each year we find that many have some degree of expertise already in the problem they want to research, which makes accessing and understanding college-level texts much easier.

Another dimension that makes this work so powerful for a teacher is getting to see how students who are very shy are able to rise to the occasion and speak about the topic at length. Sometimes, a student whose shyness is overwhelming in the beginning ends up able to speak about the topic more thoroughly than me, or compellingly than any academic. It’s amazing to see these shifts. It’s incredibly powerful to see students make use of academic tools to not only identify the root causes of a problem, but to think of possible solutions as well. They’re prepared to make changes in their community, and confident enough to communicate with city officials about what the problem is and what they expect their representatives to do about it.

YPAR also changes the way that they perceive their community. Our students are so bombarded with messages of, “Boyle Heights is a ghetto. Get out of the ghetto.” I often hear students say, “Now I want to go to college and come back, to be a part of my community so I can change it.” They’re not saying, “I want to get out of here”—they’re learning to appreciate and growing to love their community, whereas before they only thought of it as an empty, negative space. Now, they’re seeing it as a space of possibilities.

What is an example of an issue that your students have examined through their research?

One topic that students looked into this year was the rights of garment workers. Many of the parents of my students work in the garment industry. Some students interviewed their parents about their experiences working extremely long hours in the garment industry. Oftentimes when the children get home from school the parents are working. My students found that their parents’ rights at work are often being violated, and they looked into strategies to fight for these rights. Most of the garment workers are women, and many are undocumented. My role was to connect the students with the Garment Worker Center, where they conducted more interviews with workers. The students used GIS to map the hotspots of the garment industry within Los Angeles; they identified where workers are unionized, and how they fight back against violations, such as filing grievances against their employers. I learned from my students that undocumented workers are still entitled to filing grievances, which is a very big deal.

Through this project the students became very active with the Garment Worker Center, attending their events, including a protest. Now these students can teach younger generations about these issues. They created a workshop to teach the younger kids, so they in turn can help inform their parents about their rights and not be intimidated by their employers. The students and their families come to understand that there are spaces of support for them, and that they can work towards changing their workplace experiences. The students also understand their parents a little bit more, including how they feel and the ways they are exploited.

Were any of the parents able to hear the students’ presentations?

It’s difficult for a lot of our parents to get to school during the day because of their work hours, but yeah, a lot of parents were able to make it. Every year, the parents are very appreciative for this project. At first some parents are uncertain what is going on because students work through weekends and after school to get their research done. When they talk to me and I explain what the project is and why we do it, their immediate stance is unconditional support. They’re proud and appreciative. I haven’t had a parent that didn’t feel proud, especially when they see the presentations—the students sound very scholarly, and they’re teaching other, younger students on top of it. So there’s always a lot of pride.

Of course, there are other topics as well: students have researched environmental justice issues, immigration issues, and women’s rights issues, amongst others. Since we leave it open to whatever they want to research, it remains a challenge for us as teachers. We have to stay a step ahead and are always trying to find the latest stories, findings, or trends for each topic. I’m always thinking about who I might contact so that my students can have access to experts and their knowledge.

We’ve been talking about classroom activities that help your students concretize a vision of creating community and standing in solidarity. In addition to this, you are active with clubs on your campus that also try to create similar spaces, albeit outside of the classroom. Why is that so important for you?

I sponsor the MEChA club at Roosevelt High School, and I was in MEChA during high school myself. I also was very active in MEChA during my undergraduate years at San Diego State as well. As a high school student, it was a place where I could learn and be supportive of others while feeling supported. It was a community where I could explore and gain a deeper understanding of my life: “Okay, I see different forms of oppression all around me, but what does it mean and how do we do something about it?”

MEChA emerged out of larger student organizing efforts in the 1960s, a lot of it from Boyle Heights. Students came together at the University of Santa Barbara in the late 1960s, and they created El plan de Santa Barbara which then developed in the into El plan de Azlan. The student activists sought to create spaces where they could learn about politics and their culture and promote a college-going environment. As a high school student, MEChA definitely did that for me, and continued to do so throughout my college years. At San Diego State I helped organize a high school youth conference every year, and it was really there, through MEChA, that I learned a lot of my activism and organizing skills.

When I became a teacher, I spent my first year teaching middle school and I started a MEChA club by myself, because I felt like it was important to pass along that legacy. The middle school students became very involved in their community—this was when HR4437, a broad anti-immigrant law, was being proposed. When I became a high school teacher here at Roosevelt, I just felt that it was a necessary thing for me to do. I didn’t do it my first two years, but I did take students to the high school MEChA conferences here at UCLA. My second year at Roosevelt, my students started asking why we didn’t have a club, and from there it all happened very quickly.

I was taught that every MEChA meeting should be organized around some sort of political, cultural, or college-related topic, with the aim of educating people about the problems at hand and possible solutions. The leadership within MEChA is tasked with educating members on pressing political and cultural issues, to encourage college-going cultural beliefs and practices, and also to act as a pulse of the community. They are constantly trying to capture what’s happening in their community and what the primary concerns of community members and students are. Students at Roosevelt High School are dealing with issues of concern on our campus, but they’re also looking to me for guidance about getting involved with broader community issues. As an advisor, whatever issues the students raise with me are the issues I’m responsible to find resources for; from there, my responsibility is to bring us into the larger web of organizing.

For example, when DACA came out, my students said, “How do we bring a DACA clinic here?” I went to the Dreamer workspace at the UCLA Labor Center at MacArthur Park. They decided to place a clinic at Roosevelt High School. I don’t think it was because I was there at that meeting, but my students were very engaged with that. Whatever the students request, I go out and try to find resources for it. I feel that if I’m not creating a space for students to engage in activism, I’m not being myself as a teacher. When I moved to LA, I didn’t have an activist community. It was depressing for me. I did have friends that were also social justice teachers, but I had to find a way to bridge teaching to activism. You can’t just insert yourself in spaces. It’s an organic process.

You need to create community.

Yeah. I didn’t know where to go, or who to be with. As soon as I started building with my students and organizing, I felt joy again as an educator, because I felt like I was doing my job. For me, it’s not just the academic part—there’s also the re-imagining part. How do we change the reality that we live in? The answer is within the youth. Creating that space for them to promote these ideas is really important for me. Working with other social justice teachers and hanging out in their classrooms during lunch helped us affirm our identities and build a collective. That was really exciting for me because I felt finally safe and encouraged to do this type of teaching. As a social justice teacher, simply building curriculum is exhausting if you don’t have this community of educators. You’re not using the textbook, and if you are, you’re using it to critique what’s happening. But you’re not following a prescribed curriculum.

I imagine that when you’re following the students’ concerns and dreams, they’re going in all different directions. And following all of them is a lot of work.

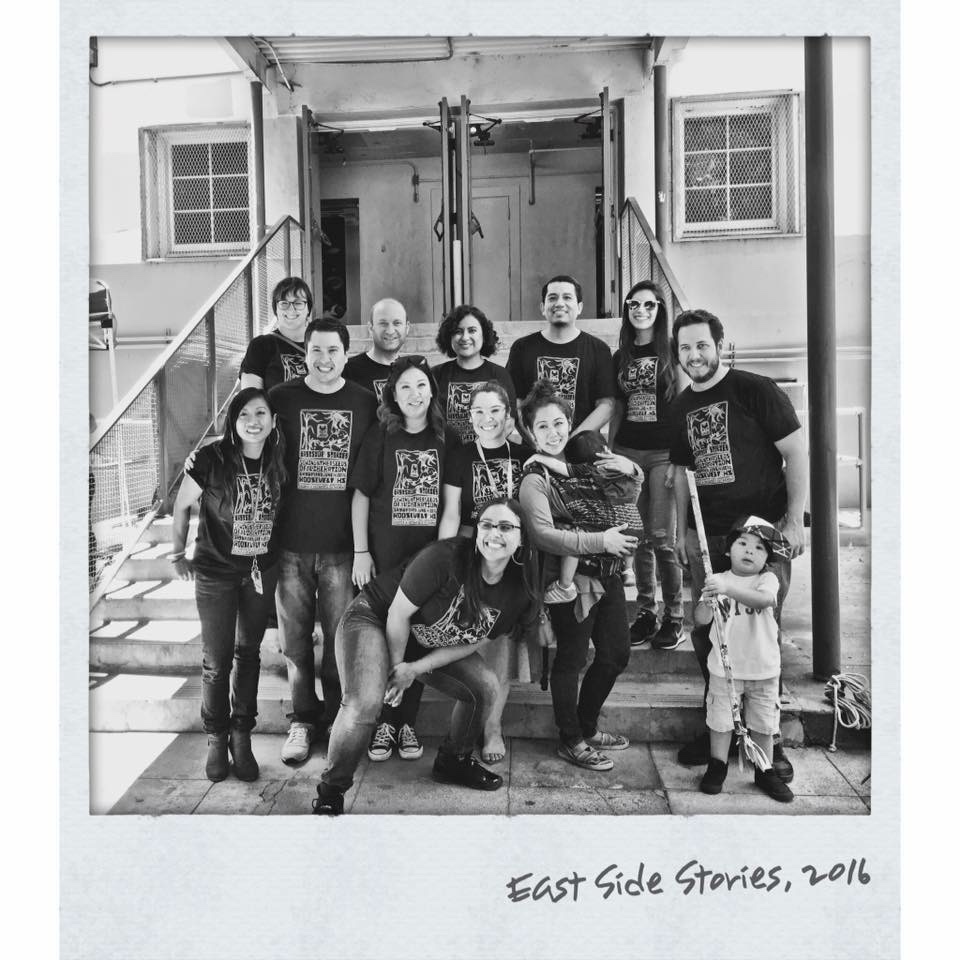

It’s a lot of work. You don’t know if you’re doing the right thing. You need a space where you can talk to other like-minded educators to bounce ideas off them. Sometimes it’s getting or offering a hug, because the situations that we go through with our students are difficult and daunting. We’ve created a space where we can be human, in an educational system that tells us we’re crazy for trying to change the world. We call that collective space “Politics and Pedagogy.” It’s been a space of healing and a space of growth for us. Because the work we all do is so different, we began to merge it together and we created the East Side Stories Conference, where the youth are the workshop presenters.

We try to bring in young, inspirational people of color to be keynotes speakers. They could be teachers or scholars, or student activists. We also bring in parents. We hold the conference once a year, on a Saturday, and we get between 300-500 attendees. It’s just a celebration. We have lunch and entertainment together, and it helps create that community within the school. This is work that we do simply because we love doing it. There’s no money attached to it, nobody pays us extra. It’s our grassroots approach to creating community and building pride within the community.

I recently saw one of your tweets where you wrote, “As educators, it’s our responsibility to ensure that students can live and learn without fear.” This tweet came out in the context of a campaign to force ICE to release one of your former students, Claudia Rueda. Can you talk a little bit about what happened, and how you and others responded?

Claudia has been an organizer since she was 15 years old. Her mother was detained by ICE in April, and she immediately began a campaign to bring light to the situation. When I saw Claudia working on her mother’s case, I asked my students, “Do you want to participate in this campaign?” A lot of them began tweeting, posting on Instagram, making phone calls to the Border Patrol, and talking about the case to their families. Eventually, Claudia’s mother was released.

But, in May, ICE agents arrested Claudia. We felt that Claudia was targeted because of her successful campaign. We’ve seen this before, with other immigrant youth activists—when they organize, they become targets and so do their families. With Claudia in detention, we began another campaign: calling, tweeting, Instagramming, whatever we could do with social media, whatever it took.

Roosevelt teacher Gillian Russom and I reached out to our union, UTLA, for support. We had this conversation with UTLA, about the importance of teachers being at the forefront as advocates for our students in these times, under Trump. UTLA partnered with us to organize a press conference at Roosevelt High School. They helped us acquire permission from the district, put together a press release, and get press there. Claudia’s professors from Cal State LA came out for the press conference, as well as some of her other former teachers, many of whom had previously not been involved in any sort of organizing or activism. That was beautiful to see, because it taught me that everybody’s way of being involved is different. People can become involved in community organizing at any time in their life.

We don’t know when those moments are going to come.

We don’t know when. It’s important for us to keep that at the forefront, I think.

And what happened through this organizing?

Claudia was released, though it wasn’t directly from the work that we did. But I feel like our work made a statement that teachers are allies, and families and students can look to us as allies and advocates. Claudia’s release resulted more from the work of the Immigrant Youth Coalition, because they were fearlessly at the forefront of this campaign. We just added ourselves in solidarity to this movement.

I should say that I don’t consider myself the voice of immigrant students, or of anybody in particular: I consider myself an ally, an advocate, and a supporter, in service of my students. If anyone requests my support or my help, I will join in that movement, but I always recognize who is really leading the cause. It’s really the immigrant youth that are leading the effort.

What do you feel like your students learned through that campaign?

I think they learned that unity is important. There are so many forces that try to portray an “us versus them,” or first-generation versus second-generation dichotomy, and by coming together as a community, we can change that dynamic. Whatever we imagine, whatever we manifest, if we come together, we can make a difference. If laws are unjust, because we live in a democracy, it is the people’s will to change that reality. I think that they understand in a deeper sense what it means to live in a democracy, and what it means when people come together in the struggle to make a difference. Change is possible. I think they learned hope, as well.

What makes you hopeful at this moment?

I don’t know where I gather this hope, because it’s tough. It’s emotional. I was at a museum exhibit yesterday with my niece that covered the 1992 LA riots. I was trying to explain to her, “This is redlining. This is what police brutality means.” She’s six years old. After we were done with the exhibit, she said, “I need to dance. This is a lot. I need to dance.” I think that’s what keeps me hopeful—making sure that we dance, that we understand that there’s so many forces that are against us, but to enjoy life, and to seek culture, and to seek each other’s company, and to embrace each other in unity, and find ways to not get stuck in that messy sense of oppression and fear, but to convert that into a beautiful struggle where we’re learning from each other. We’re creating with each other. We’re building with our students. That’s why I say the youth have all the answers. Because in the middle of all of this chaos and stress, they always have a way to laugh, and to play, and to make me laugh, and remind me that learning is playing, that learning is fun. And, no matter what, we need to keep moving forward with our heads up high, and with a positive view on life.

You gave me that today. Thank you, Mariana.

Thank you.